Courtesy of Fondazione. Photo by Attilio Maranzano

London

Carsten Holler: The Double Club

January 2009

Since the early 1990s, Brussels-born Carsten Höller’s activity as an artist has stretched from designing carousels and developing narcotics to producing goggles that allow viewers to see the world as it really is, upside-down. The Stockholm-based artist shapes experiences more than objects, and the objects that he does produce resemble scientific tools, precision instruments in stainless steel, untouched by the dirt of daily life. This professionalized approach depends upon a high level of specialization, consultation, and research. (It is unsettling, though perhaps unsurprising, that in a previous life Höller trained as a phytopathologist with a special interest in insect communication.) A great deal of this research-based practice is directed toward understanding the construction of experience. How can we say that what we’re feeling is real at all?

The Double Club (2008-9), his most recent project, ventures far from the laboratory, with the Stockholm-based artist recasting himself as an itinerant entrepreneur, part philanthropist part self- appointed cultural attaché. Conceived by Höller but financed by the Fondazione Prada, The Double Club inhabits a Victorian warehouse complex down a dingy backstreet of Islington in North London. Here, the favored strategy is separation over miscegenation, with the menu, decor, and music policy receiving equal space but split down the middle. Cheerfully ignoring the formula for culinary fusion that became popular in restaurants a few years back, Höller’s hope is, presumably, that division will engender dialogue.

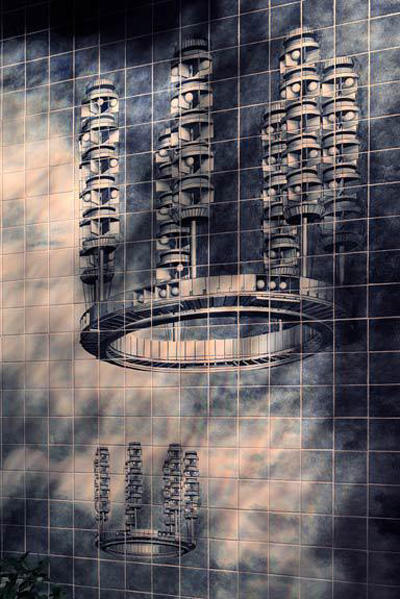

Open for just six months, The Double Club comprises three rooms: a bar in a spacious covered courtyard, a small nightclub with a revolving stage, and a cozy restaurant in which designer tables share space with molded plastic furniture. Built from imported wood and corrugated iron, the Congolese bar is modelled on Franco’s in Kinshasa and sits back-to-back with a polished-copper pub, above which a pink neon sign announces the “Two Horses Riders Club.” The nightclub section can be glimpsed through a two-way mirror surrounded by an azulejo mural of Russian architect Georgi Krutikov’s 1928 drawings for flying cities (a work that Höller previously quoted in a piece shown at the 2002 São Paulo Biennial). In the club itself, an LED-illuminated palm tree refers to Chez Ntemba, a popular Kinshasa nightclub. One half of the menu, in the meantime, is braised beef and terrines, the other kossa kossa (spiced shrimp), fumbwa (salted fish, peanuts, and yam leaves), and pig trotters. Höller plays curator, too, selectingğalong with Germano Celantğa curious range of works by Andy Warhol, Carla Accardi, and others, alongside Congolese artists Chéri Samba and the Kinshasa- based Monsengwo Kejwamfi.

Equally split down the middle is The Double Club’s music policy, with Western nights on Fridays and Congolese on Saturdays. Still, sometimes this equitable approach doesn’t seem to run all the way to the top. The layout was realized by young London-based architecture studio Carmody Groarke; the Western interiors were managed by Kram/Weishaar (who designed Prada’s concept store in Beverly Hills); while Höller himself dealt with the Congolese section. Similarly, there appears to be little Congolese input at management level: the enterprise is overseen by Mourad Mazouz, founder of Momo and Sketch, and Jan Kennedy, who founded Quo Vadis and ran Damien Hirst’s ill-fated Pharmacy restaurant. For a project that makes much noise about showcasing the best of two cultures, it is both telling and uncomfortable that The Double Club won’t venture beyond two affluent cities — from London it tours to the Rem Koolhaas- designed Fondazione Prada in Milan —nowhere close to Central Africa. Which leaves us with the following dilemma: should The Double Club be considered a brave artwork or a canny franchise, a politically loaded exploration of ethnic marketing or yet another example of finely produced cultural imperialism?

Importantly, The Double Club’s opening coincided with one of the most difficult years in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s fraught history. Following the 2008 failure of a seventeen-thousand- strong UN Peacekeeping Force, at the beginning of 2009 around forty-five thousand Congolese are dying every month due to famine and disease. Since the Second Congo War began in 1998, over 5.4 million lives have been lost, more than in any conflict since World War II, and fighting continues in the east despite a peace treaty in 2003. Indeed, since the Belgian colonization of the DR Congo in the late nineteenth century, in which around half the population was killed over the course of twenty years of ruthlessly surveilled rubber production, the country has seen virtually continuous fighting. Prada seems to have realized only late that, as brand alignments go, civil war may be just a little too edgy; the venture was originally floated as the “Prada Congo Club” but rechristened “The Double Club” when its opening last November coincided with a further three-thousand troops being sent in to the DR Congo by the UN. A percentage of the profits are being donated to the UNICEF charity City of Joy. Laudable as this is, however, it’s not clear whether the club was originally planned as a charitable venture.

Far from a rose-spectacled tourist, Höller has been traveling to Kinshasa for some years now, having recently made a film about the music scene there. But while his hopeful attempt to compare and contrast different approaches had a troublesome genesis, more problematic is why the Congolese and Western models are being treated as opposites in the first place. Drinking aside, visitors to The Double Club are unlikely to see double, as these visions of a restaurant/bar/nightclub aren’t so different. The copper-plated dividing line enforces a split that many of the clientele just as happy to party in Dakar as nearby Shoreditch (where the unfortunately titled club Favela Chic can be found) won’t recognize. Höller favors what he has referred to in the past as “influential environments,” though few visitors to The Double Club will be pushed toward anything so troublesome as doubt or disorientation. At least as interesting as The Double Club’s replication of the DR Congo is the scrambled construction of its Western half. Where exactly is this meant to be? And when?

Courtesy of Fondazione. Photo by Attilio Maranzano

In “Politics of Installation,” a recent essay printed in issue two of e-flux journal, Boris Groys criticizes the popular view that installation art “democratizes” an artist’s practice, challenging the supposition that it acts in the name of a certain community. The large-scale installation is far from democratic, Groys continues, because “the visitor leaves the public territory of democratic legitimacy and enters the space of sovereign, authoritarian” control. The visitor is “on foreign ground, in exile.” The Double Club may profess to act in the name of the DR Congo at least insofar as much-needed charitable donations are concerned but in practice it’s more concerned with enforcing the divide between social models that are neither so specific nor so separate as it hopes. Using Groys’s terms, it’s difficult to forget that it is Höller and Prada who maintain sovereign control over the venture, which doesn’t care to stray too close to the troubled state that it borrows credibility from. Far from being on foreign ground, or feeling productively lost, the visitor to The Double Club feels all too comfortable.