Berlin

Far Near Distance

House of World Cultures

March 19–May 11, 2004

The word eikon, which simply means image in classical Greek, can now refer to almost any sort of vaguely emblematic representation. The fact that “icon” also signifies a graphic symbol on a computer display screen aptly reflects its usage in discussions of Globalization, where it’s shorthand for something appropriated simultaneously in radically different contexts, suggesting an intrinsic power within the artifact per se: Islamic veils, Arafat, Sid Vicious, etc. The older, Orthodox-Christian denotation is also relevant, not only in terms of transcendence and aura, but also in that the churchly icon lays no claim to verisimilitude. The difference between the sign and the real thing was underlined by way of, among other things, an aggressively anti-realistic use of perspective. This was not, however, to the benefit of the artist’s personal style; on the contrary, the more uniform and derivative the icon, the better.

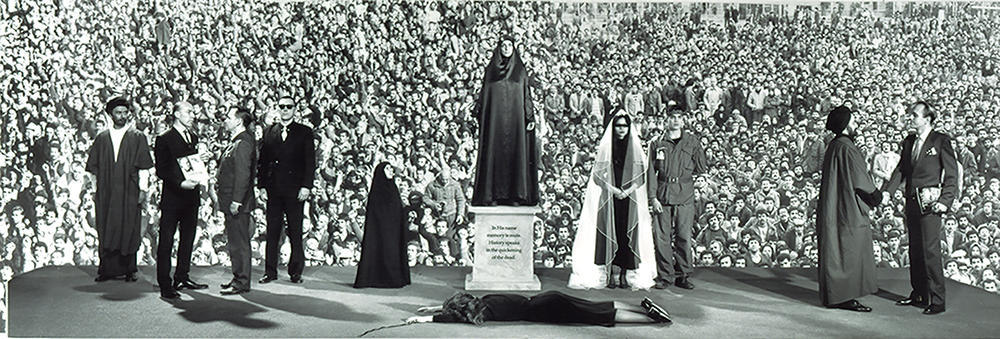

At the exhibition Far Near Distance: Contemporary Positions of Iranian Artists at Berlin House of World Cultures, SHAHRZAD placed an icon in a glass display case (Jamaran, 2004). Initially, photographer Shirana Shahbazi — one of the three members of SHAHRZAD, besides designer Manuel Krebs and myself — was invited to participate by herself, but her artistic proposal, offering no reference to Iran, was rejected. Shahbazi made a second proposal, this time as SHAHRZAD, to reconstruct a glass display case at the Khomeini museum in Tehran, which includes slippers, a Qoran, clerical robes, official documents and a bottle of Chloë, by Karl Lagerfeld. This, we hoped, might allude, among other things, to the reduction of artistic efforts to symbols of regional realities, to state-sponsored games of representation in Berlin and in Tehran and to the prerogative of curating entire regions.

Other works at the exhibition included Farhad Moshiri’s Living Room Ultra Mega X (2004), an overwrought, hyper-aestheticized homage to post-revolutionary nouveau riche aesthetics, consists of gold-colored, kitsch knickknacks. A number of other works equally gain in undermining their own documentary potential by leading not simply to national tokenism and testimony, but to a potentially ornamental or iconic reading, a sentimental safari through a gaudy peepshow extravaganza dubbed “Iran,” e.g. Mehran Mojaher’s photographs Traditional Photography Studios (2003), Shahram Entekhabi’s colossal, glittering key to paradise (Kilid, 2004), or Ali Mahdavi’s mummified animals draped in pompous religious robes (2000).

As many a museographer has pointed out before, the teleological underpinnings of Western museums mostly suggest that Euro-america is what history was striving for from the start, culminating in the happy Here and Now of women’s rights, parliamentary democracy and post-Duchamp standards in art. Any frictions or oppositions stemming from an Outside are cast as something Not Quite There Yet, as epistemologically belated guests, sure to join us at the dinner party in due time.

In this sense, the glass display case is a useful tool. It underlines the crass measures of de-contextualization and iconification that are glossed over in regional exhibitions, and echoes the art exhibition’s historical roots in the Gruselkabinett and the Museum of Natural History, but also brings analogies with cultural merchandising into play. Further, the glass case epitomizes the Western claim to superiority qua higher museum standards, where security and climatic conditions are guaranteed. (Interestingly, the latter-day version of the vitrine was introduced only in 1929, by pioneer ethno-museologist Henri Rivière, prior to whom the cases on display were original transport boxes.)

Following the opening of Far Near Distance in Berlin, the Iranian PEN Association quickly launched an online protest, claiming SHAHRZAD had assembled original items from the Khomeini museum, but then withdrew the petition after some of its leading members resigned over that very document. A host of other associations took up the cause, showering the Berlin House of World Cultures with anti-Khomeini leaflets, draping our installation with an adhesive black foil brandishing political slogans, besmearing and ripping up catalogues, then demonstrating outside the institution, threatening to storm the events at the museum and prompting a sizable police presence, as the online debate among expat Iranians spread from Berlin to London and on to LA. Luckily, the debate did not overshadow the exhibition in its European reception, which was, in any case, lukewarm and subdued.

The debate over the SHAHRZAD project has raised questions far more subtle than anything our collective or any other protagonists could claim to have intended. Must an art installation be politically called to account for the pictorial denotations the audience sees as pertinent — and what are the criteria that determine this political pertinence in the first place? What is, say, more fundamentalist or reactionary: an Ayatollah Khomeini display case, or a photo of a veiled broom, which artist Shadi Ghadirian sees as a sincere homage to women’s place within the home — or philosopher Daryush Shayegan’s ruminations on the “poetic Iranian psyche” (to name two other contributions to the event).

For an earlier exhibition which was held at a gallery space within a Hamburg nightclub, the SHAHRZAD collective printed posters with the slogan “Death to America” garlanded with collages of pop icons such as Mandela and the Dalai Lama. The work drew all sorts of commentaries, the most remarkable of which was the accusation of pandering to trite, middle-of-the-road Euro-liberalism, such as juvenile anti-Americans in black-and-white Palestinian neck scarves. The said critique came from a DJ who used to play what he called International Dance Music, but now only plays Western material, since he got tired of people clasping their hands above their heads and wiggling about in mock Bollywood gesticulation, or indulging in improvised belly-dancing and such. His critique touched a nerve at the very core of SHAHRZAD’s preoccupations: the enticing malleability of iconic images and slogans in an international context, i.e. their role in the construction and domestication of the exotic — and their potential to transcend that very dynamic of cultural tokenism.

The question, then, is how to participate in an exhibition which caters to the very cosmopolitan spirits that prompted our DJ friend to refrain from internationalist aspirations altogether — without repeating the patterns one set out to expose. One of the ideas behind the SHAHRZAD project, in any case, is to pinpoint and re-contextualize icons that draw attention to patterns of truth production, and sometimes even offer ornamental hues of truth of their own, but without laying claim to any unambiguous, didactic frame of reference. But that aside, it’s also a question of strategies of critique: must the most pessimistic, devastating reading prevail — perhaps in the name of one’s postcolonial credentials — or should possibilities of irony and subversion consciously be placed in the foreground?

HKW (Haus der Kulturen der Welt) www.HKW.de

Many thanks to artist Andrea Thal for her helpful references to vitrine history.