The Cairene spring arrived in mid-May, in the form of perfect days — breezy yet warm, the kind of weather that makes you want to run around the city on foot. It was a few anxious weeks before midterm elections for the Shura Council, and every inch of available space was plastered with political posters. Building facades, bridges, and electricity poles: the faces were everywhere, bearing down on me from every direction, imploring or commanding, struggling to wrest my attention from the movie posters and advertisements for cell phones, sunglasses, and hearing aids.

The biggest, glossiest posters always belonged to candidates from the National Democratic Party, the president’s party, though there were plenty of them for Tagammu (“Rally”), the perennially underfunded party of the left. Tagammu’s candidates were a study in forbearance; they looked almost comfortably shabby, resigned to their impending loss. The Muslim Brotherhood is technically barred from participating in Egypt’s “secular democracy,” but you can tell the “independent” candidates running with the Brotherhood’s blessing by the words al Islam howa il hal running across the bottom. “Islam is the answer.”

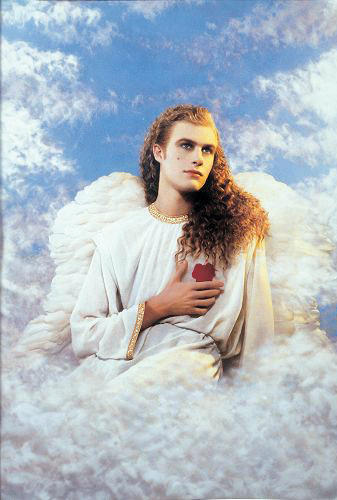

One of the most striking posters depicted a candidate for the affluent district of Kasr El Nil. I noticed it one afternoon while walking down the west side of Zamalek, along the Nile. I had just turned onto Mahmoud Mokhtar Street, by the opera house, when I came across a wall lined with the most sublime images. Framed in a laurel wreath was the face of a blond-haired, blue-eyed, fairskinned angel, emerging from or ascending to a heavenly blue sky as wispy clouds floated peacefully above. It was an icon, though not the kind you see at church. It seemed almost satirical, an homage to some kitschy object of divinely inspired lust, like l’Ange Blessé by Pierre et Gilles. I went closer to read the fine print: al Islam howa il hal.

The marriage of pomp, politics, and religiosity is nothing new. For decades now, sweeping banners of President Hosni Mubarak have shaded our boulevards from the sun, while halos form around his image through clouds of carbon monoxide. I grew up in that shade. Imprinted in my mind’s eye is the president’s iconic face, his infamous black Aviators, The Road Ahead reflecting back into the infinite realm of his pupils. It’s a mesmerizing image of control; I try to be wary, but I can’t suppress a fuzzy feeling of awe whenever I see it.

Which, to this day, is often, but never more so than in the summer of 2005. It was a milestone event — the first “multiparty elections” in Egypt’s history, the first presidential election of my adult life. And he was everywhere. If a shop didn’t have a billowing image of Mubarak covering every possible crack and crevice on every wall, pillar, and post, it was asking for trouble. Mubarak’s visage was omnipresent, looking out from nursery schools, up from rooftops, pasted on buses, and tucked inside textbooks. Other parties were competing, but it was mostly symbolic; the NDP’s campaign was masterminded by Marawan Hamed, the savvy young director whose next major project would be the best-selling film in the history of Egyptian cinema, The Yacoubian Building. Most of the Mubarak posters were distributed via the good offices of the state. If I had ever entertained hopes of getting out from under his image, the inundation of our public spaces that year dashed them forever.

Of course, there’s more than one Mubarak. In the capital, his most recent portrait is set against a Matrix-inspired emerald green galaxy. This is Mubarak 2.0, the One whose instantiation reflects the values of the tech-savvy world of Cairo’s aspiring middle-to-upper classes.

Further up the Nile, icons of the president assume more phantasmagoric shapes. In one arresting depiction, Mubarak appears upright, full-figured, shadowless. He is a true demigod, straddling the worlds. To his left, pyramids; to his right, skyscrapers. His right arm sweeps away to the horizon, index and middle fingers slightly tilted, raised in blessing. Fighter jets splinter into the sky like fireworks beneath a bright orange nimbus: the sun god, Ra. If there are cults in Egypt today that still believe in the old gods, that seek to restore the majesty of the pharaohs, Mubarak wants their vote, too.

It there were such a cult, it might well have a chapter in Qena, a governorate in the heart of upper Egypt whose denizens line the walls of their homes with votive portraits of themselves — riding a plane, sailing away on a cruise ship, making the hajj. These are people who live amid ancient tombs and temples, just outside the valleys of the Kings and Queens. It’s not hard to imagine that the narratives in Mubarak’s hand-painted political posters speak to viewers in the south in a manner we may be numb to in the city.

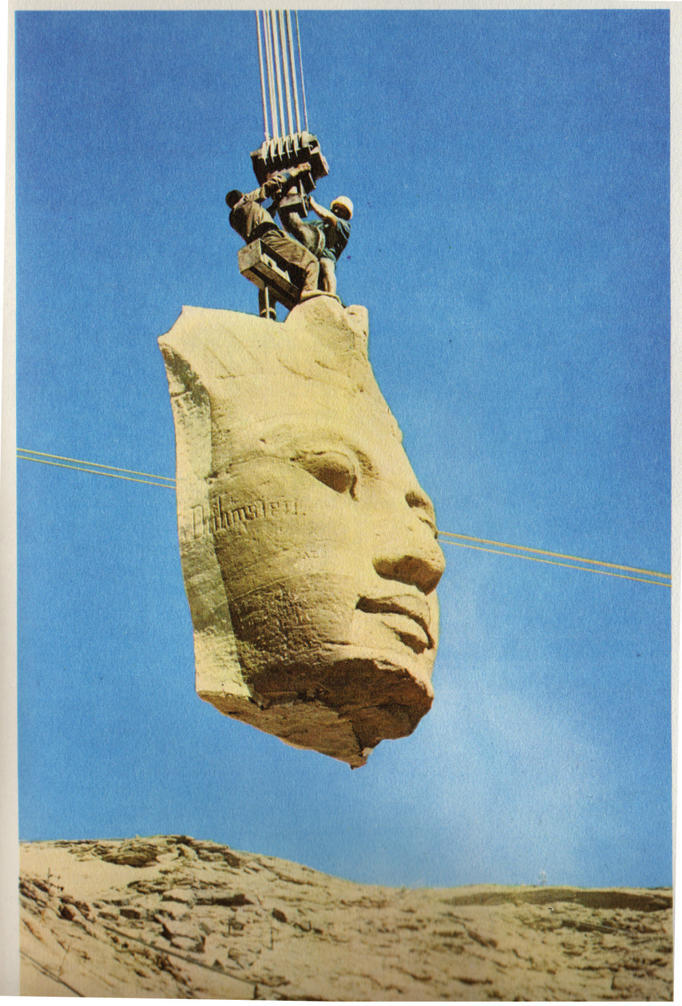

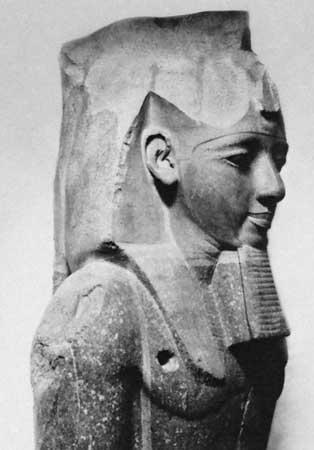

When Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power in the 1950s, he sometimes equated himself with Ramses II. As Ramses had expelled the Hittites from Egypt, so Nasser had expelled the British; Ramses built colossal statues, temples, and vaults that would last for all time; Nasser would have his dam at Aswan, a monumental project that would change the topography of the land forever, creating the greatest lake in Egypt. Ramses, son of Ra, became the greatest of the kings of Egypt; and so Nasser, his successor, would refract that ancient glory.

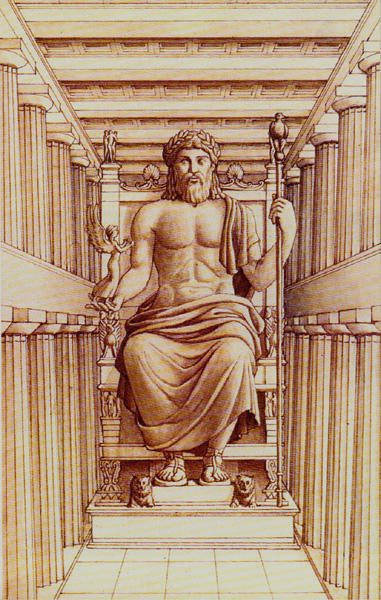

Perhaps it’s merely a function of nostalgia, a longing for something before my time, before this time, but the old iconography of the glorious Nasser seems more powerful to me than that of Mubarak. His image was invested with hope — for honor, equality, victory. His icons were not only the stuff of political campaigns; they also appeared in private homes, on desks and bedroom walls. One of the most common images people hung in private spaces was a black and white photograph of Nasser draped in white linen, making the pilgrimage to Mecca. He is standing upright, the cloth sweeping down his otherwise naked body, hands folded in prayer. He looks to the side, the object of his gaze obscure to us, as a crowd of men, also draped in linen, look toward him. In that iconic image he achieves his ultimate majesty: on the road to the holy of holies, looking for all the world like Zeus.