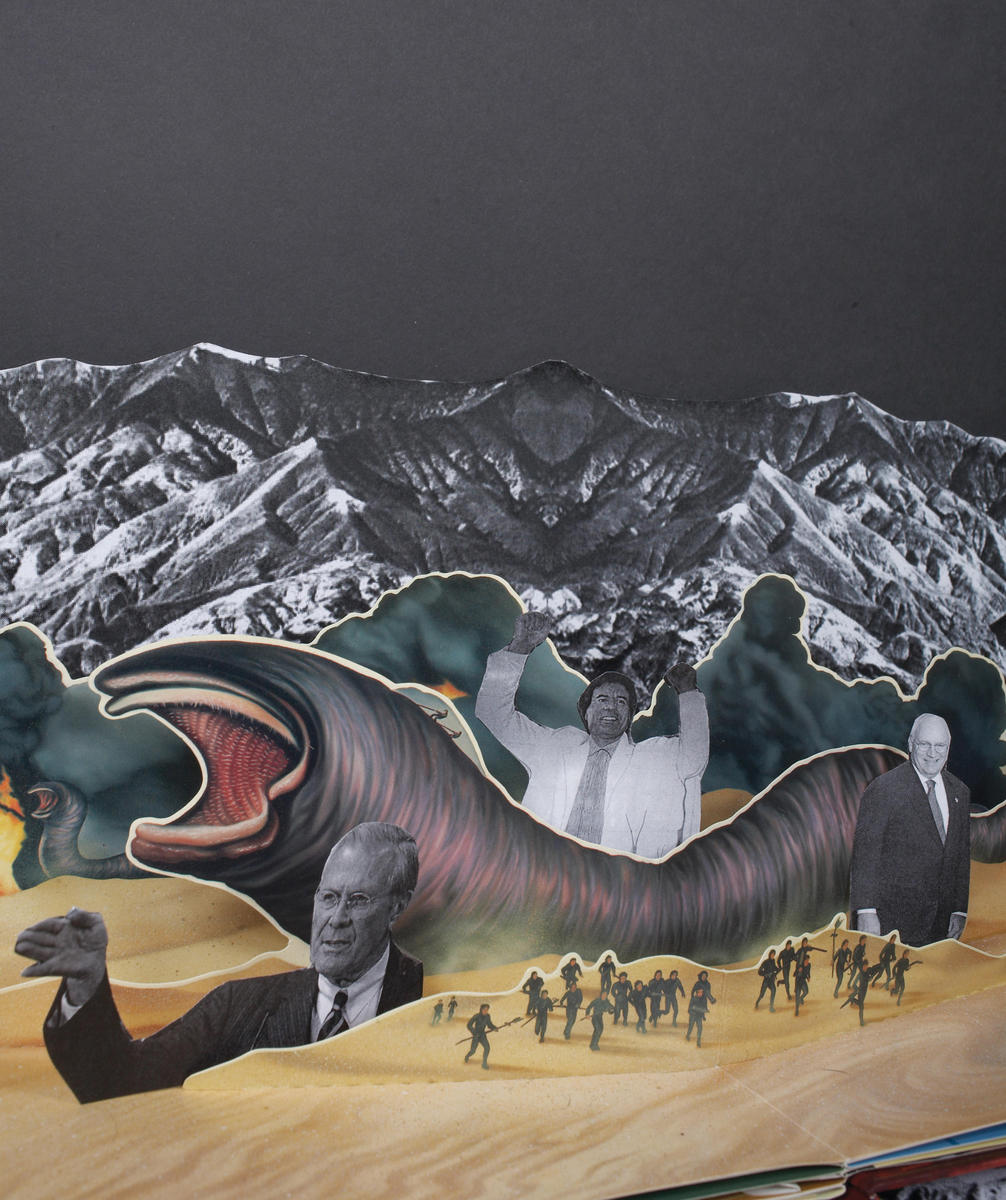

Donald Rumsfeld was born in 1932, which means that when he turned fourteen and started reading science fiction, Frank Herbert had not yet written his epic 1965 novel, Dune. The same is true of all those touted as the architects of President Bush’s aggressive Middle East policy. Bespectacled to a man, with a penchant for epochal policy shifts, grand sweeps of human history, and forced marches of progress, the neocons have about them the whiff of the middle-school war-gamer, the high-school debater, and the barely pubescent science fiction reader. More’s the pity, then, that Frank Herbert published his intergalactic political potboiler well after the policymaker-as-young-nerd put down Joseph Campbell’s Amazing Magazine and picked up Machiavelli. Had those boys read Dune, they might have thought twice about occupying Iraq. Not least because of the sandworms.

The sandworms are the giant worms that live in the depths of the desert of planet Arrakis, né Dune. They produce a spice that allows humans to predict the future. The galactic economy depends upon spice-borne prescience; the power that controls the desert planet Dune and its spice, therefore, controls the universe. The Fremen, the veiled nomads of the desert, call the sandworms Shai Hulud [eternal thing] — but, really, trying to understand the sandworm, not to mention the plot of the entire Dune series (six books, three millennia, one worm-man god-emperor), from a capsule summary is as frustrating a task as understanding Iraq’s sectarian conflicts by reading around the blogosphere.

Dune’s central importance at our current historical juncture is twofold. First, it postulates, however implicitly, that in the distant future the only remnants of twentieth-century human life will be Arab in origin: a desert planet, an invaluable natural resource, veiled and fanatical nomads, a prophet known as the Mahdi, an intergalactic jihad. Each object of significance in the Dune universe has its obvious parallel in the Arab Word: spice is oil; the nomads, Bedouins; the intergalactic jihad, jihad. Even the language spoken by the Bedouins of Dune is derived from Arabic. The sandworms have no immediate analogue in either Arab or Islamic history; they are, one hopes, completely made up.

But the notion that Islamic Arab culture exists essentially unchanged in the year 10,000 or so is a double-edged sword, a sign of both tenacity and stagnation. As the rest of the universe has developed space travel, lasers, video-conferencing, and ebooks, the people of Dune have remained rooted in their autochthonic patterns of life: roaming the desert, locating oases, gathering spice, riding the sandworm. Their culture lies outside of progress, of technological advancement, of history. Rationales for invasion and occupation have been built on less. This is the stuff that adventure stories, earthbound and intergalactic both, are made of: Technologically superior races conquer the less motivated, the incompetent, and the gullible. A monocle is a sign of divinity; a record, the voice of God; a Bible, the profoundest of technologies; a laser-guided smart bomb, imprecise death from above.

Dune, though, manages to turn the setup for a call to arms — natives make easy pickings — into a cautionary tale. Aided by sandstorms, sandworms, a dose of religious fanaticism, and the almost complete ignorance of their would-be conquerors as to the culture and logistics of the planet Dune, the natives emerge triumphant, overthrowing the emperor and embarking upon a centuries-long jihad through the known universe. A neat, and perhaps frightening, inversion — a botched invasion of an Arab land results in the birth of a prophet, the toppling of an imperial power, and a restructuring of international relations.

Given the ease to which Dune lends itself to allegorical reading as both jihadist wish fulfillment and critique of neocon hubris, it is strange that the book has never been translated into Arabic. There was some speculation after 9/11 that the term al-Qaeda was taken from Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series; though no evidence exists that Asimov’s series was ever translated either, rumors hold that an unofficial translation may have been passed, dog-eared, hand to hand across the desert. Aside from the founding classics of the genre — notably those by HG Wells and Jules Verne — few science fictional texts have made the jump. But, given the poor track record of translation into Arabic, the dearth of English-language science fiction in Arabic is no real surprise. The 2002 Arab Human Development Report stated that only 300 books are translated into Arabic a year — about one-fifth the number translated yearly into Greek. The report depicted the state of scientific inquiry and technological development in the Middle East as lagging far behind that of the rest of the world. The image of the region that emerges from its statistics is that of a backwater placed at the center of global attention by a resource curse and constant religious ferment.

Dune’s version of a futuristic Arab culture rising victorious isn’t entirely pessimistic. The jihad yields a new order; corruption is wiped away; and technology comes to transform Dune’s harsh deserts into verdant pastures — with adequate desert kept in reserve for the sandworms, of course. A far darker vision of the future comes in the recent film Children of Men. In the final scenes, set in the very bleak and very near future, a violent protest has begun in one of the many giant refugee camps that dot England. One revolutionary calls it the Uprising — the beginning of a final, apocalyptic battle between the immigrants and the British state — but someone has scrawled Intifada in Arabic on the walls and lightly armed men face down the might of the military while yelling Allahu Akbar. The Arabs, in 2027 as in 2001 or 10,000, are angry, fanatical, and armed. Jihad and violence are the wages of Iraq, the movie insinuates, and will remain so for decades to come.

Science fiction is a poor prognosticator of the future. For every presciently imagined submarine or space shuttle, there are dozens of teleportation devices, nuclear armageddons, and forgotten promises of Soviet domination. But if the form of science fiction sometimes provides an avenue for outré imaginings of the present, it is possible that the writing and reading of speculative fiction in the Middle East may open valuable discussion of what the region, its religions, and its cultures might look like one day. Why not start by translating Dune into Arabic? African writers riffed off of Heart of Darkness for decades, subverting, inverting, and just plain trashing Conrad’s novella in pursuit of new ways of representing African life. It might be wishful thinking to imagine that Dune, in translation, would do the same thing for the next generation of Arab writers. But the possibilities are delightful to imagine: flying taxis in Cairo, Sufi outposts on Saturn, telepathic Bedouins — even peace in the Middle East!