The tourist I was, once, waited for the dawn train from Rabat to Casablanca. It was January, but he’d been caught unprepared by a brutal chill, down from the Atlas, a dry and biting cold. This was why people traveled, he thought, to do stupid things that tested what they could bear, who they were. The trip had been full of moments of aboveaverage stupidity, like buying hashish in the park at Marrakech, and not even for himself. He’d smoked it anyway with the students who sold it to him, to make sure it wasn’t goat shit and they weren’t cops.

They had been sitting behind a low wall off one of the broad alleys, a scent of flowers strange in winter. They wanted to know who he was, and he told them he was French. “Personne n’est français,” said their crew-cut leader, inhaling and passing the joint. The tourist inhaled, too, and tasted saliva. No one was French. It was undeniable.

Just as no one was really American, or Moroccan, for that matter, except the Berbers, and maybe not even them. My ancestors were from Poland, he told them. “Juif, donc?” He would not deny it. But he couldn’t help imagining them trying out their very own conversion of the Jew, either. The hash had made him paranoid, so he took off with the rest of the foil-wrapped cube. They told him to go with God — all people of the book, some better than others. Walking away, with their eyes on him, he was reminded of Central Park’s Sheep Meadow back in high school, the private school kids and the public school kids, buying and selling, terror, shame, pride, self-contempt. Set foot in Africa and feel like a teenager again.

Then there’d been the solitary walk through Fez at dusk, while Quentin and Anne rested at the hotel. (Perhaps that was the first time they’d slept together?) At one of the cafes in the modern city, a boy he imagined to be a more beautiful, Berber version of himself came up to him speaking Spanish, then switched to French. The boy bared his teeth, said he wanted to fuck him. “Je t’encule, tu vas voir, ça sera beau.” And then, sizing it up differently, “Tu aimes les filles, je comprend, pas de problème, moi aussi.” The boy promised to take him to a whorehouse where they’d watch each other taking turns, a different version of homosexuality; he only needed to make a phone call, but that required, for some reason, a lot of cash up front. The tourist wanted nothing, or rather it was enough to know that this was happening. They settled for tea and cigarettes. When he turned the talk to Berber nationalism, he caught some of his own fear reflected back at him in this boy-man so seemingly eager to be his friend.

This last self-imposed test, the long night of the train station, mostly involved sitting still. It was too dark on the platform, and he had nothing left to read, anyway. The day before, killing time in a garden above the sea with a plate of almond cookies, he’d burned through the secondhand copy of L’Immoraliste he had been saving for the journey. Better anyway not to read, but to think back on what he’d seen and heard, replaying the experiences, affirming them before they vanished in the airport lounge at Charles de Gaulle or the line at customs or that other train, to New Haven, some twenty-four hours in the future.

He began to take notes, but even the ink oozed slowly in the cold, and all he could think about was the unfairness of the chill. He hated unnecessary expenditure and had refused to pay for an extra night at the hotel. Instead he had gone over to the station at midnight to wait the four hours for the train. The station itself was well lit and slightly warmer, but that was no longer an option.

A painfully thin man had wanted to talk to him, his watery, cataract-scarred blue eyes gleaming over a thick beard and shrunken cheeks. Christ on the cross, the tourist thought. But he wasn’t Christian at all, it turned out. The man had been a religious student; something had happened to his body while at the madrassa. He wasn’t well, he said. His friends had it, too. They had been very close. One should be lucky to have such friends with whom one can share everything.

The ex-Talib didn’t know what he had, but his faith had decayed with his body. The Moroccan government wouldn’t tell him, and the tourist didn’t have the heart to suggest he was probably dying of AIDS. All meetings with strangers are meetings with angels, he thought, but I cannot be this man’s angel of death. He gave him most of his remaining dirhams instead. It was a tactical mistake, since just about everyone still at the station at that hour seemed homeless and in need of money, and they were watching him. It was too much to bear, all that need, the suffering he was powerless to do anything about, the raw rubbing of so much humanity against him, plucking at him. He imagined they’d strip him naked if he let them, eat him alive like zombies. That’s what they are, the living dead in those films — the poor, coming to get you. Saying no to people was the hardest thing, and he’d never been good at it. To each according to his needs, from each according to his ability. But what if the needs are bottomless? Thank God he was on his way back to America, where these things were all hidden away, at least from him. The only thing to do was head down to the platform, with that studied air of urban purpose, although the train was still hours away. It was too cold for them down there; it was starting to be too cold for him.

He paced, he rubbed his hands, blew on them, thrust them into the pockets of his mackintosh, the only coat he’d packed. That was another stupid rule: only take what you can carry on your back. He’d amended it to include an item of hand luggage, but that was for stuff to carry out; he’d brought almost nothing with him. Bargaining for the handcrafted and handwoven was what one came to Morocco for, of course, recovering the human element in making, selling, buying. He and his friends had toured the tanneries, the shops of metalworkers and weavers, gone hunting in the medinas to test their own eyes, emerged with the spoils to prove it. North Africa, not only another place but another time — that would be his slogan for the tourist bureau, if they asked him for one. He liked the idea of traveling backward, had always preferred old places to new ones.

That had been the real point of the trip, to escape time, specifically the Western calendar. He and Quentin and Erik came up with the plan while watching the news about the millennium bug, the vague reports of terrorist threats and impending breakdown of the global order.

“Idiots will do something just to make sure the prophecies work out,” Quentin said.

They’d agreed to go onto an alternate calendar, trading New Year’s Eve for Ramadan, and cracked jokes about how no one would notice in Marrakech if the computers stopped. The only problem would be if they couldn’t manage an ATM withdrawal. Anne said she was coming, too, but then she and Erik split up and she insisted on making the trip, and Erik decided not to come.

The tourist jumped in place, shadowboxed, replaying a fight they’d seen in the square at Marrakech, tempted to blame Anne for his imminent death by freezing. If she hadn’t come, she and Quentin wouldn’t have spent the vacation falling in love, and he wouldn’t have left Fez ahead of schedule to give them time to themselves, which was why he was in Rabat that night, waiting for the train to Casablanca and its airport.

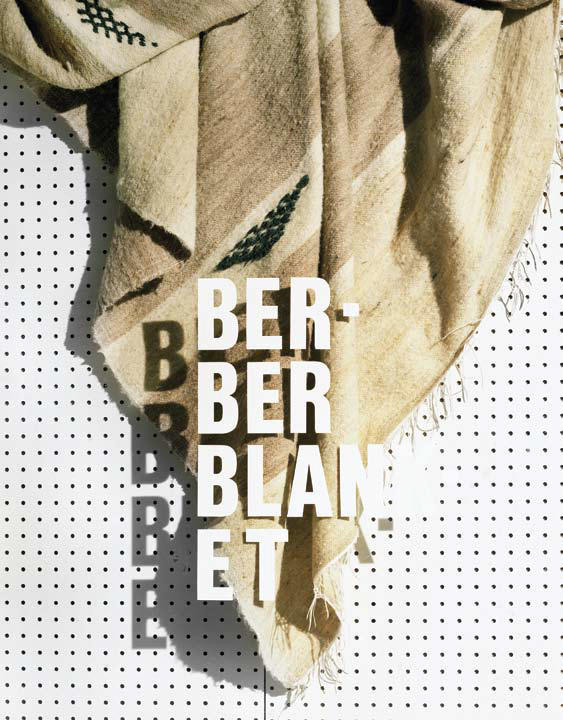

His anger couldn’t warm him for very long, so he decided he would put on all of his clothes, even the dirty ones. At the top of his bag, right there when he opened it, lay the Berber blanket. He couldn’t believe his stupidity. He unrolled it to its full length, about eight feet, and then wrapped himself in it the way he thought he’d seen it done in a photograph of Sitting Bull. Then he pulled it up over his head. Where it touched his skin, it prickled like two-day stubble, but still he wound it tighter.

“It’s camel hair, my friend,” the salesman had said. A lighter singed the fringe, the burned tassel held out to him to sniff. Perhaps this was what burned camel smelled like? He would never know, but he enjoyed the show, that and the simplicity of the thing, broad bands of alternating brownish shades, from a beige-white that was almost the color of the better-preserved houses to a rich brown that looked like the gates to Fez’s old city, as seen from the mountains above. It was land-colored, he decided, and from that moment it became the Souvenir, the thing he’d keep for himself. The bargaining was a formality, a performance to keep face. “I’m only a poor student,” he said, “even for an American.”

“Ah, then it’s perfect. We call this the ‘student carpet.’”

Forty dollars made everyone happy. At the station, though, it merely kept him warm. He huddled under it, looking like a Christmas-pageant camel with embroidered tribal markings, imagining himself a shepherd of the Atlas, until the train came to take him back to twenty-first-century America.