Artists’ Magazines

By Gwen Allen

MIT Press, 2010

By the end of the 1960s, Artforum had become the country’s dominant art magazine — part Sears Roebuck catalog for the McLuhan generation, part promotional vehicle for a clutch of New York abstract painters and the formalist critics who favored them. Younger artists came to see it as embodying a system that favored galleries and dealers over artists and viewers, and whose primary interest was maintaining its own power. In order to talk back to critics who misunderstood or ignored their work, artists went about founding magazines of their own, especially in New York City, the bastion of the (increasingly wealthy) status quo. Rather than indulge in a singular, authoritative perspective (consolidated by a “house style”), these magazines — Aspen, 0 to 9, Avalanche, Art-Rite, FILE, and Real Life among them — provided a space for artists to colonize the discourse, and do so in their own voices, however idiosyncratic or naive or choleric.

Gwen Allen’s Artists’ Magazines chronicles the rise and fall of these publications, and a sampling of their contents. Artists like Robert Smithson, Dan Graham, Mel Bochner, and Vito Acconci created magazine art where criticism had once been, emphasizing the materiality of language, denying its ability to communicate. (Graham’s Schema, a site-specific instructional piece published in a variety of magazines in the Sixties and Seventies, is a paramount example; it consisted of a template to be completed by the editor, in accordance with the magazine’s typography, design, and layout, producing a new work in each iteration.) They published texts that were oftentimes unresolved, propositional, exploratory — concerned with process, not product; conjecture, not conclusion. Allen, an art historian at San Francisco State University, describes their “articles” as “guerrilla tactics that attempted to commandeer the commercial publicity of the magazine by manipulating its form, content, mode of address, and audience.”

While this suggests a certain measure of calculation, much of what is compelling about these magazines is a product of their messiness, the substitution of passion for professionalism, and the sense — inevitably inflated — of the importance of the present moment. Of course, there was also the desire to kill the father, to unseat the ancien régime. The experience of the sublime proffered by abstract painting is sucked of its power in the pages of these magazines, which sought to embody conceptual art’s focus on the contingencies of time and space, and the activation rather than supplication of the viewer.

For Smithson, the magazine was a site not unlike the Great Salt Lake, the page a material not unlike rock or sand. He described the magazine in his patent geologic vocabulary, as “a circularity that spreads into a map devoid of destinations, but with land masses of print… and little oceans with right angles.”

Transforming the magazine into a venue for art was not just an aesthetic strategy, but part of a utopian program. The art historian Benjamin Buchloh, who for a time edited Interfunktionen, voiced the sentiments of many editors and artists: “We were deeply convinced in all earnestness that the elimination of the commodity object from the work of art and the reduction of the work of art to linguistic proposition had a tremendous pedagogical and political potential and an egalitarian democratic implication that would have vast consequences in terms of the collectivization of aesthetic experience.”

Aspen perhaps best represents that dream. The so-called magazine in a box was started in Aspen, Colorado, in 1965 by Phyllis Glick, a New York journalist and editor who initially wanted Aspen to reflect the town’s alternative cultural scene. Within a couple of years, however, it became one of the century’s richest experiments in publication, and perhaps the first veritable new-media magazine. Each issue was published in a box that included films, texts, images, and interactive projects. Aspen 5+6, edited by critic and artist Brian O’Doherty, included recordings of Marcel Duchamp reading “The Creative Act” and Max Neuhaus performing John Cage’s “Fontana Mix-Feed,” Susan Sontag’s “The Aesthetics of Silence,” a sculpture by Mel Bochner in the form of seven translucent grids (to be put together by the reader), and a construction kit for a miniature sculpture by Tony Smith. The experience of Aspen mirrored Roland Barthes’s argument in “The Death of the Author” (originally published in the magazine), being incumbent upon the reader rather than longer plotted and linear.

To Allen, Aspen also harnesses the democratic potential of the form: “Rather than cloistering art from everyday life, the magazine released it back into the world, countering the timeless, contemplative visuality of the modern museum with a distinctly temporal, interactive experience.”

If Aspen is the most forward-thinking magazine discussed by Allen, and also the least like an art magazine, Avalanche seems, in hindsight, to be the most conventional. Started by Liza Béar and Willoughby Sharp in New York City in 1970, Avalanche combined the parochialism of a community newspaper with the cinematic design and attention to personality that were characteristic of the era’s new-journalism stalwarts. And yet it also epitomized the artists’ magazine: Béar and Sharp used extensive, probing interviews and lavish portfolios to convey the voices and working processes of artists, in what Béar describes as “investigative reporting that aimed to understand rather than to expose, in which the questioning voice was closely attuned to the artist’s sensibility.” (Avalanche’s entire print run was recently reissued by the publisher Primary Information.) And while the magazine was moored to the SoHo scene it had helped foster — each issue carried news of neighborhood goings-on in the form of “rumblings” — Béar and Sharp placed the work of their clan in the context of new art from Europe, Canada, and California. Avalanche epitomizes the dominant characteristics of all these magazines: the ambivalent relationship, but constant concern, with publicness; the effort to disseminate the work of artists without commodifying it; the desire to create alternative spaces for art that were nevertheless linked dialectically to the institutional spaces they opposed (and eventually subsumed by them; see Documenta 12 Magazines, 2007).

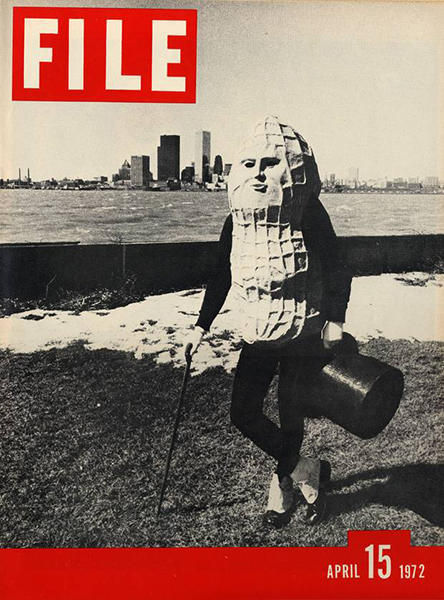

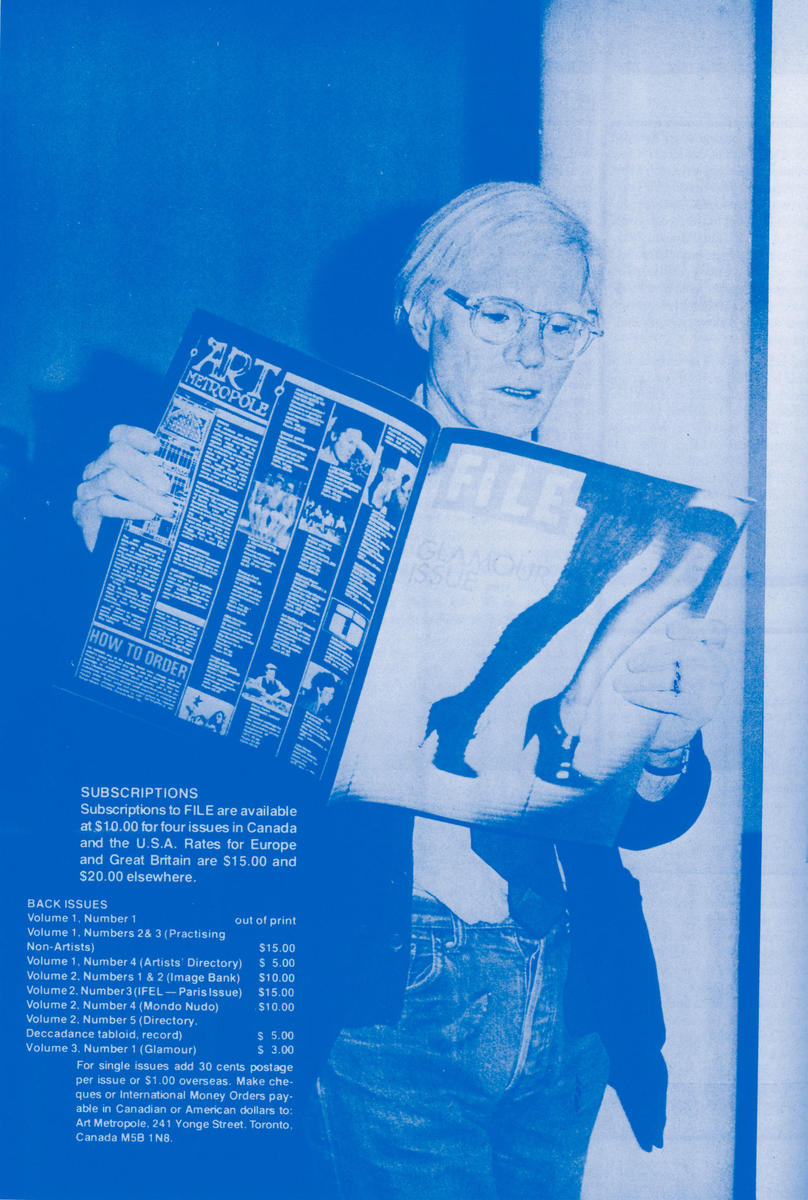

By the 1970s, artists’ magazines were being shaped in part by a disillusionment with the promise of mass media, especially in light of conceptual art’s hermeticism. “Whatever minor revolutions in communication have been achieved by the process of dematerializing the object,” art historian Lucy Lippard wrote in 1973, it had become clear that “art and artists in a capitalist society remain luxuries.” The later magazines discussed by Allen seem less intent on revolutionizing the relationship between art and mass media than on self-consciously tweaking and critiquing it. FILE, started in 1972 by the Toronto collective General Idea, was a campy performance of mass-media tropes. The artist-editors pulled much of their material from the pages of the popular press, cannibalizing its images of the good life to produce its own subversive myths — mostly about itself, whether that meant raunchy diaries from the Canadian mail-art scene or reports on the never-ending preparation for a great spectacle called the 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant. “If Life mirrored life,” Allen notes, “FILE mirrored Life.”

Real Life, founded in New York City in 1979 by Thomas Lawson and Susan Morgan, circled around the so-called “Pictures generation” artists, whose work often dealt with appropriated imagery (often sourced from mainstream magazines), and was concerned with “the possibility that reality might evade representation, that it might exist outside of the visual economies of both art and media,” as Lawson put it. Though these magazines continued to insist that art must engage a greater (if hazily defined) public, the work they published remained obscure; the democratic potential of the form rarely infiltrated its contents.

The world of these magazines can be understood as linked to what historian Anthony Grafton has called an “information regime,” the study of which considers “not just the formal content of ideas but the institutions and practices that enabled them to be created and transmitted.” By doing so, Allen inevitably holds up a mirror to our own institutions and practices. In the past few decades, the galleries, museums, and magazines against which Avalanche and FILE railed have become expert at incorporating, homogenizing, and commodifying expressions of dissent and difference; ironically, these moves seem to have finally expanded art’s public reach (or at least its sphere of consumption). The publication of Artists’ Magazines reflects a broader resurgence of interest in the form, due in part to a nostalgia for the deeply felt intellectual communities they represent — and, as Allen recognizes, a concurrent, and paradoxical, fetishization of these magazines as art objects, and as an essential part of the twentieth-century avant-garde canon.

While this process may have drained the artists’ magazines of the Sixties and Seventies of their radical potential, the environment that birthed them is in many ways analogous to our own, and they become newly relevant when considered as precursors to present-day experiments with the latest new media. While we like to think of the Internet as somehow, automatically, birthing such communities, breeding innovation, and spewing forth novel ideas, it tends to only offer the faintest facsimiles. And while we hail the democratic potential of today’s information technologies, few artists have figured out how to make compelling work that capitalizes on it. Allen’s book clarifies the potential and the limitations of the Internet as a medium for artwork, and the magazines she discusses provide a framework for considering emergent forms of publication. Artists’ Magazines affords a view not just of alternative spaces but of alternative futures; they are fecund, unorthodox, genuinely social, and not yet inconceivable.