Whenever I met Abu Hamza at the immigration detention center in Lukavica, on the outskirts of Sarajevo, he carried a brown diary with him, filled with notes neatly inked in Arabic and the language formerly known as Serbo-Croatian. One day, as we sat in a small meeting room with the door open, I noticed that he had written “THE ABYSS” in English across the top of one of the pages of his diary.

Perhaps he was rehearsing some new human-rights slogan to raise awareness about the plight of people like himself, Islamists from the Arab world who had fought alongside the Sarajevo government during the 1992–1995 Bosnian war. Or maybe it was a sardonic reference to his ongoing predicament: being indefinitely detained without charge as a “threat to national security,” backed up only by secret evidence. It turned out to be simpler than all that. The Abyss, James Cameron’s 1989 sci-fi disaster thriller about a deep-sea alien encounter, had been playing on the TV in the rec room the other night. It intrigued him. “I love fantasy films,” he said. “As a believer, I know that we are not alone in the universe. There must be other forms of life.”

Abu Hamza’s interest in fantasy films wasn’t terribly surprising. Over the years, he and I had talked regularly about miraculous happenings during the war: bodies of martyrs that smelled of musk, angels intervening on the side of the Muslim bodies of martyrs that smelled of musk, angels intervening on the side of the Muslims. During a mujahid assault on a Serb-held hilltop, the opposing forces inexplicably aimed their artillery upward and fired into the sky. In captivity, the Serbs reportedly told the mujahideen that they had been shooting at horsemen in white attacking them from the air. The Balkan landscape lent itself to some enchantment: even mujahideen with little time for miracle tales were enthralled by the white-capped mountains and lush forests; one Saudi journalist titled a wartime travelogue “The Journey of Fire and Ice.”

At the end of the war, most of the Arab mujahideen — seen as mythical figures by some, reviled as monsters by others — left Bosnia. Many returned to ordinary lives, some pursued jihad in other besieged Muslim lands, while others turned against Arab regimes and their superpower sponsor. In contrast, Abu Hamza and a few dozen of his mujahid brothers took Bosnian wives and settled in a formerly Serb village called Bočinja, where they tried to create a proper Islamic community. Many of the Arab volunteers, especially those from the Gulf, had been disappointed by the discovery of openly pork-eating, alcohol-drinking Bosnian Muslims. So Bočinja was intended to be an oasis of sorts, a self-sufficient, right-living polity, with a health clinic, a radio station, and a mosque of its own, outside the country’s official Islamic institutions. They even experimented with communal agricultural work. Many families were started.

There were tensions, of course — not only among the Serbs left in the village, but also among the Muslims. Relations between one Egyptian ex-fighter and his German convert wife broke down after he took an Albanian woman as a second spouse in hopes of conceiving a child. The ensuing drama was the talk of the town. Both the man and his ex-wife are back in Germany now. He was interrogated by the CIA in Indonesia on suspicions of Al Qaeda ties but never charged; she published a tell-all memoir about being married to a mujahid.

There was also the battle of the satellite dish. Abu Hamza possessed the only private satellite dish in the community. Some of the brothers questioned why he got to have something expressly forbidden to the rest of them. But Abu Hamza insisted that his case was special. Unlike most of the others, Abu Hamza spoke the local language fluently; the satellite dish was important for knowing what was being said about them in the media and to expose his children to the wider world. In the end, he had to put his foot down: “It’s either me or the satellite dish.”

It turned out that what was being said about them was largely hostile. Debate, such as it was, centered on whether this odd Islamic commune was a terrorist training camp or merely a backward fundamentalist enclave. Bosnia may have a Muslim plurality, but after decades of socialism, Islam is as much an identity as a prescription for religious practice. And in any case, postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina is officially a multi-ethnic state with a labyrinthine and redundant set of governors and institutions — presidents, prime ministers, parliaments, ministries — representing the nation’s Bosniak (Muslim), Croat, and Serb populations. It is all supervised by a mélange of Euro-American acronyms (NATO, the EU, the OSCE, OHR, EUFOR, and more). One of the supposed bright spots in this dismal scene has been the hope of one day being welcomed into Europe, as neighboring Slovenia and Croatia have. The existence of Bočinja, full of men with huge beards and prayer caps and women in niqabs, did not seem likely to enhance those prospects.

In the summer of 2000, NATO peacekeepers evicted nearly all the mujahideen from the village, returning their homes to the original owners. The Arabs of Bočinja scattered. Some left the country while others, like Abu Hamza, found new homes and girded themselves for the struggles to come. (As a prominent ex-mujahid, Abu Hamza would have been imprisoned and tortured if he returned to Syria.) September 11 came not too long after, and the campaign against Arabs intensified. Another Egyptian, the self-styled mufti of Bočinja, was arrested and shipped off to Hosni Mubarak’s torture chambers. Six Algerians were sent to Guantánamo even after a Bosnian court cleared them of charges of plotting to attack the US and UK embassies. (The famous US Supreme Court decision granting habeas corpus to Guantánamo detainees bears one of their names, Boumediene.)

Abu Hamza became an internationally famous symbol of “radicalism” lurking in Bosnia. In 2008, the State Department’s annual terrorism report claimed he was on a UN list of Al Qaeda and Taliban affiliates, though it turned out they had confused him with another Abu Hamza, a convicted Egyptian terrorist in the UK (who, unlike the Syrian Abu Hamza, is missing two hands and one eye). The facts were off, but no matter: Washington’s preferences were clear. Within months, Bosnia’s highest court upheld a decision stripping Abu Hamza of his Bosnian citizenship. The immigration police took him away two days later.

Abu Hamza was the very first inmate at Lukavica. He was already in custody when the prison had its official ribbon-cutting ceremony. Soon he was joined by others, some of them people he knew from Bočinja or from the mujahideen battalion; others were Arabs who had never fought. None of the long-term inmates had come to the Bosnian war directly from their home countries, so their itineraries were more telling than their origins. One Algerian I met had made the hajj to Saudi Arabia in the early nineties to flee the civil war in his country, then overstayed his visa and found work with Islamic charities. His job took him to Peshawar and then to the Balkans, where he was compelled to quit (something about money and his Saudi bosses) and ended up joining the Bosnian army. Foreigners in the army could easily obtain citizenship — but as with Abu Hamza, a special multinational commission working from secret evidence revoked his citizenship. A few months after we met in the detention center, a court restored the Algerian’s citizenship and he left the prison. Refugee turned pilgrim turned humanitarian turned mujahid turned prisoner — by now we should just call him an immigrant, right? His story was hardly atypical.

As far as Bosnia and its Western sponsors were concerned, the detention center was supposed to be a last pit stop on the Arabs’ way back home. But human rights groups, citing the likelihood that the Arabs would experience imprisonment and torture (or worse) upon returning, have fought the efforts to deport these men and challenged their indefinite detention. Abu Hamza has spent more than three and a half years behind bars. Despite winning his case in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg in February, no end appears in sight.

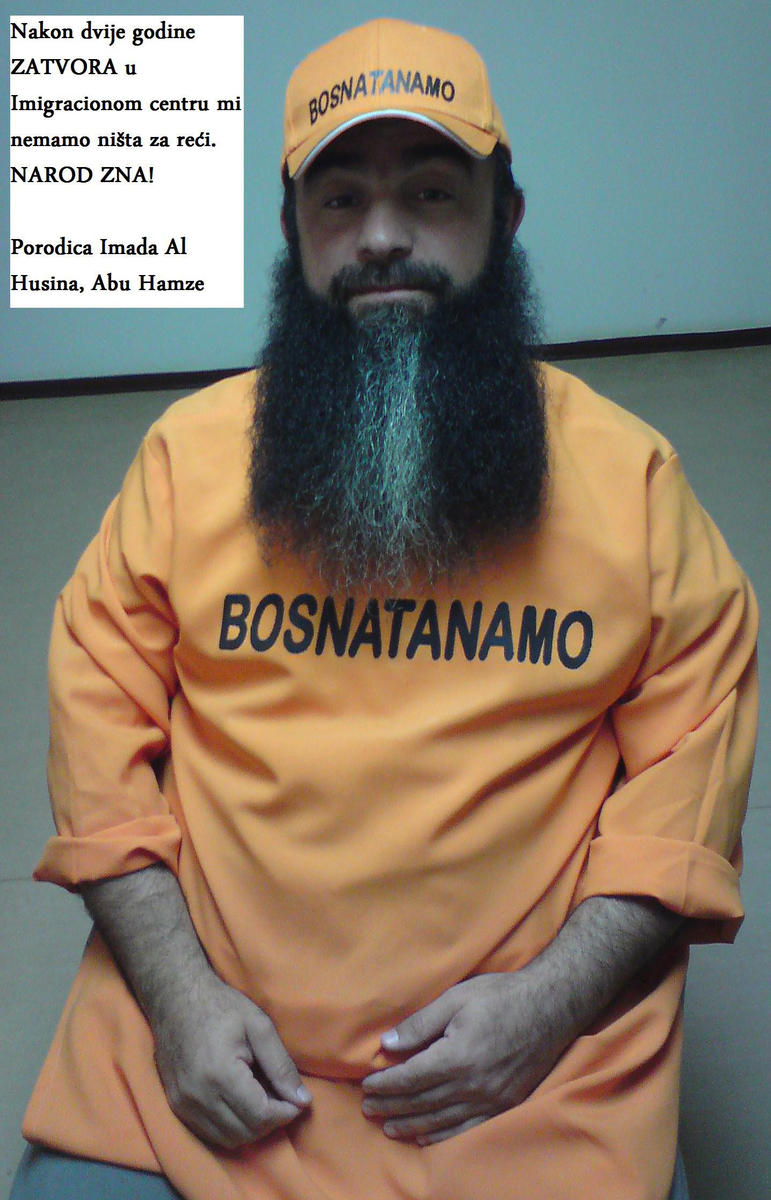

To dramatize his plight, Abu Hamza took to wearing a long jalabiya and a baseball cap, both dyed bright jumpsuit-orange and both emblazoned with the word “Bosnatanamo” — an odd mash-up of Bosnia and Guantánamo. During the 2010 elections, his family released a photo of him in full Bosnatanamo regalia, captioned: “After two years in prison in the immigration center, we have nothing to say: THE PEOPLE KNOW!” “The people know” was the campaign slogan of the SDA, the largest Bosnian Muslim nationalist party; Abu Hamza’s family spun the trite phrase into an uncomfortable reminder of debts unpaid, suggesting that the selling out of the Arab mujahideen who helped Bosnia during the war would be remembered, and perhaps punished, by the Bosnian electorate.

The response to the Bosnatanamo campaign — and to the plight of the Arab detainees generally — has been a collective shrug. Even for Bosnian Muslim nationalists, the issue has dragged on for so long and seems so trifling in comparison with the country’s problems that it’s hard to muster anything more than vague sympathy. Abu Hamza and his comrades are a reminder of a time when Europe turned a blind eye as Bosnians were slaughtered, when Muslims of conscience came to fight on their behalf. But that was nearly two decades ago, and in light of everything that has happened since, it’s a memory many Bosnians would prefer to leave behind.

It so happens that Abu Hamza is an inconvenient reminder of more than one ideological era. Born Imad al-Husin in Damascus in 1963 (everyone calls him Abu Hamza, after Hamza, his first-born son), he arrived in 1983 to study medicine at the University of Belgrade, one of thousands of such students from young postcolonial states who flocked to what was still one of the great capitals of the Non-Aligned Movement. The most famous of them was the writer Abdelrahman Munif, whose Cities of Salt quintet charted the rise of the contemporary petrostate; Munif did a doctorate in economics on a Ba’ath party scholarship in the late 1950s. Decades later, the Ba’ath party had branches in nearly every university town in Yugoslavia. Abu Hamza remembers an “election” organized by the Ba’ath for a few dozen Syrian students in the Adriatic port city of Rijeka that resulted in a defeat for Hafez al-Assad; the stunned embassy in Belgrade immediately dispatched an official to reeducate them.

Marshal Josip Broz Tito died in 1980, but the nation he had championed remained a beacon for international students until 1991, when Yugoslavia fell apart and the world of Non-Alignment was turned inside out. While pursuing the project of a greater Serbia, Slobodan Milošević continued to claim the mantle of Yugoslav internationalism, making common cause with Saddam Hussein and Muammar Qaddafi. Yet it was bilingual students from socialist-leaning Arab states like Abu Hamza who played crucial roles as translators and intermediaries for Islamist aid workers and volunteer fighters arriving from the Middle East. These old Non-Aligned ties never totally vanished: during last year’s uprising in Libya, ex-Yugoslav workers flooded out of the country, only to be replaced by the arrival of ex-Yugoslav mercenaries to fight in Qaddafi’s forces. As NATO bombs fell on Libya, a right-wing Serbian nationalist party held a rally in Belgrade to show its support for its erstwhile ally.

Banners like Non-Alignment and Islam can be taken down and rolled up as circumstances dictate, but people often get left behind. “Foreigners” have been playing increasingly prominent roles in many of the post-socialist states. Bosnia’s first ambassador to Japan was a Ghanaian doctor; in 2010, a Palestinian ran for parliament on the ticket of media tycoon and political upstart Fahrudin Radončić’s party. Two half-Palestinian brothers play for one of Croatia’s top football clubs. In the streets of Bucharest earlier this year, protesters chanted, “Arafat!” — not Yasser but Raed, a Romanian doctor of Palestinian birth who led the opposition to efforts to privatize the country’s healthcare system.

All this history — spliced and remixed into strangely labeled eras like “post–Cold War,” “post–9/11,” and now “pre–Arab Spring” — may now seem as quaint and disorienting as reruns of old fantasy films on TV. As Abu Hamza languishes in prison, the world seems to have moved on; just look at how much satellite television has changed. Years after Abu Hamza put up his dish in Bočinja, one of his daughters got a job with Al Jazeera’s new Balkan channel. The Qatari media juggernaut is all about regional integration: its multi-ethnic staff is drawn from across most of the former Yugoslavia and broadcasts to more than sixteen million people who share the same language — or, as we are required to say so as not to offend nationalist sensibilities, three different languages that happen to be mutually intelligible. It’s not exactly a brave new world, but it is at least more interesting and unpredictable than a future filled with new James Cameron films and all the other blandishments of finally belonging to the West.