For those who rue the demise of Iran’s reform movement, a visit to the Mah-e-Mehr Institute for Culture and Art is an exercise in nostalgia. Step out of the Islamic Republic of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, with its pious, anti-western philistinism; here, in a north Tehran side street, there is a paved garden and a tastefully designed café where boys and girls can meet to drink latte and discuss, say, expressionist woodcuts. A young woman wearing a riveting lavender suit escorts you into an atrium dappled with light. There, Ali-Reza Sami-Azar, who teaches modern art history at the institute, chats to Shadi Ghadirian, an Iranian photographer. Some well-dressed Tehranis are coming out of the sculpture class of Parviz Tanavoli, the father of modern Iranian sculpture. The paint gleams. The women trail classy vapors. Mah-e-Mehr’s three owners, all of them gallerists, received permission to teach the theory and practice of art under the previous, reformist government of Mohammad Khatami. Their institute is a monument to the recent past.

Khatami’s was the first Iranian government since the 1979 revolution to concede that culture need not necessarily be an agent of the official ideology. The culture minister, Ata’ollah Mohajerani, supported writers, filmmakers and pop musicians whose work had nothing to do with the orthodox Shia theology. In Sami-Azar, a trained architect whom Mohajerani appointed to head both Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art and the government’s regulatory body for the plastic arts, the minister had a willing accomplice. Sami-Azar reduced censorship, promoted Iranian artists abroad and built institutional links with the western arts establishment. With two major shows at the museum, a retrospective of British sculpture and an exhibition of superb modern western art from the vaults, Sami-Azar showed that he was that rare commodity in revolutionary Iran: a globalist.

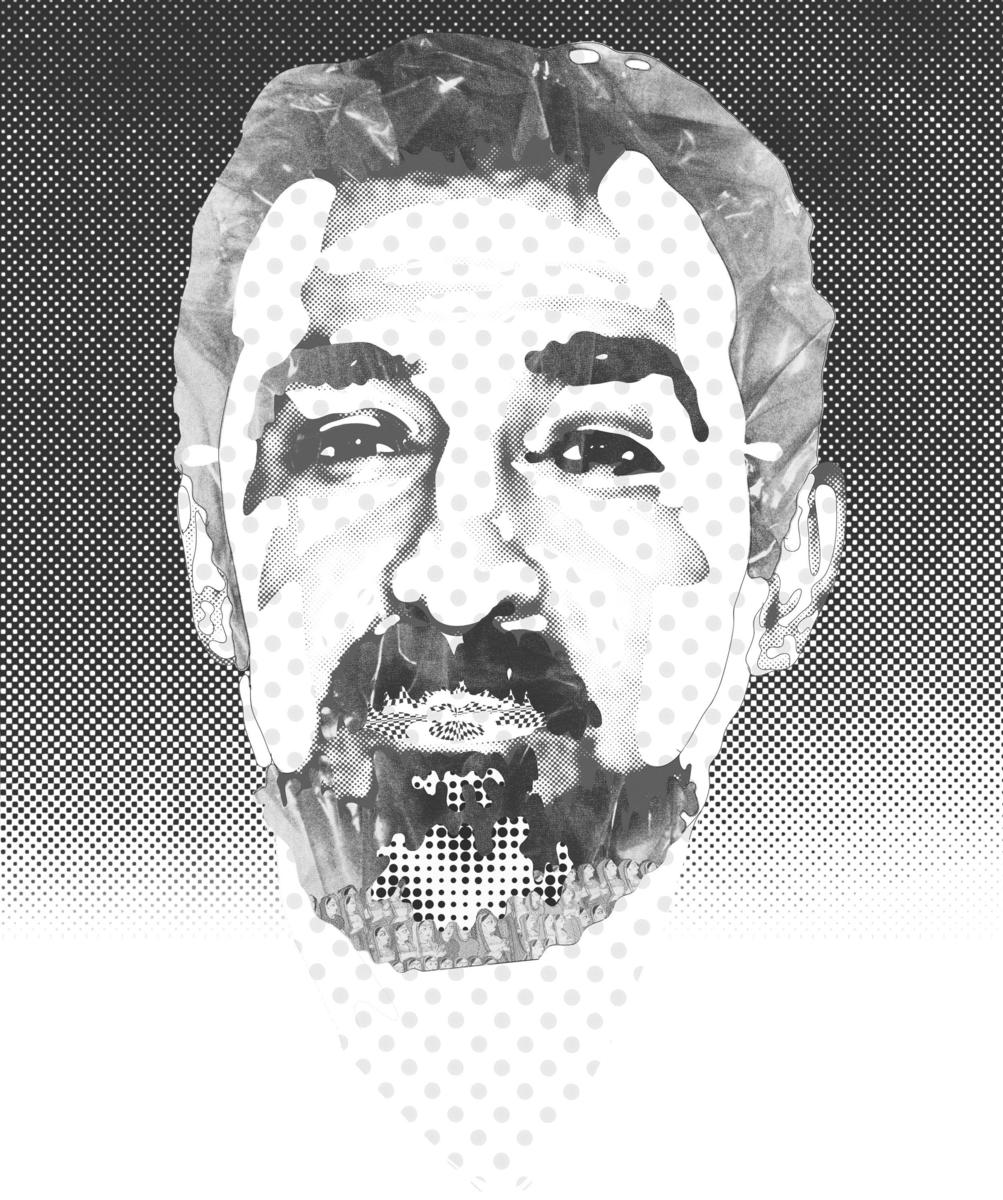

He stands before me now, jovial and energetic. His shaven cheeks and immaculate navy blue suit, and his solicitude toward the lavender lady, identify him as a reformist gallant. Sami-Azar has dark, bunched eyes and brows, which make him seem intense, but he’s an engaging, rather than a profound, conversationalist.

Christopher de Bellaigue: What has happened of note in Iranian art since Khatami left office?

Ali-Reza Sami-Azar: The answer is that nothing has happened in the arts — at least not inside the country. In the ten months since I stood down, Museum of Contemporary Art has put on two exhibitions, including the current show of Iranian photographers, and neither has been particularly well received. When I was at the museum, we staged five or six exhibitions each year and the place was a hub where artists could meet. The museum is no longer a hub.

CDB: The museum isn’t the place to gauge official attitudes.What’s going on outside?

SA: It’s the same story. Take the new government’s attitude towards Mohajerani’s plans to open modern art museums in several provincial cities. The project is gathering dust. I myself was asked to design one of the museums, in [the desert city of] Yazd. It’s now several months since I delivered my design to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, but the ministry still finds excuses to delay going ahead.

CDB: All the same, things could be a lot worse. The feared crackdown on all facets of western culture hasn’t happened. Galleries are still opening in Tehran. Exhibitions are taking place.

SA: That’s correct. They haven’t, for instance, reinstated the old system whereby a gallery needed to get a separate permit for every exhibition it wanted to hold.But I think it’s important to distinguish between the political liberalization of Khatami’s time, which has halted, and the social changes that took place in the same period, which cannot be reversed. In art, these changes are manifested in the rise of new media in art, the emergence of more young artists, many of them women, and the arrival of an identifiable community of Iranian artists, unified and talking to each other.

CDB: What about rising awareness of Iranian art outside the country? I’m thinking specifically of this spring’s MoMA exhibition, Without Boundary, which showcased the work of fifteen artists who have roots in the Islamic world, and the recent Christie’s auction of Middle Eastern art in Dubai.

SA: These are definitely encouraging developments. Of course I’m proud that the MoMA exhibition was curated by an Iranian, Fereshteh Daftari, and that no fewer than five of the artists were Iranian.

CDB: I wonder how much of a victory that really was for Iranian art. The show’s stated premise was the diversity of artists from the Islamic world, and yet by displaying them together, it seemed to reinforce the impression that they need a collective label, rather than undermine it.

SA: I don’t agree. I think one of the aims of the show, which was to challenge stereotypes about art from the Islamic world, was successfully achieved. And it showed how these people are coping with the western environment in which they find themselves.

CDB: Turning to the recent auction, where Iranian, as well as Arab, Indian, and Pakistani artists raised their profile, is there a little bit of you that’s worried by the exit of Iranian works of art?

SA: No. I’m happy that a market is growing. There was a Farhad Moshiri piece in Dubai that was estimated at $6,000 and it went for $40,000! Yes, it will take time for the market to settle. There’s still a discrepancy between prices you pay for a work of art inside [the country] and those you pay abroad. For example, you can buy a Tanavoli more cheaply in Iran than you can abroad. I’m not worried by the departure of this art. One of the things we did during the last government was remove the stipulation that Iranian works of art must get a permit to leave the country. It’s important for Iranian art to get exposure.

CDB: Where do you think Iranian artists are currently showing the most creativity?

SA: It’s striking that, in general, Iranians are very daring in photography and video, and tend to be less innovative in traditional media such as painting and sculpture. Somehow new media lend themselves to the issues that Iranian artists are tackling, and Iranian artists, or the best Iranian artists, are very issue-based.

CDB: Anecdotal evidence suggests that, for political reasons, curators are coming to Iran less frequently. The next generation is not being discovered.

SA: Iranian art is strong enough to survive. It may be that, in my own time, artists grew 94 too dependent on government support. Iranian artists are having to stand on their own two feet and, in the long run, that may not be a bad thing.

CDB: What is your dominant recollection of your final, controversial show of “decadent” western art?

SA: Well, as you know, there are a couple of pictures in the vaults, including a Renoir nude, that we couldn’t exhibit for reasons of Islamic propriety. But in my opinion, another controversial work, Francis Bacon’s Two Figures Lying on a Bed with Attendant, whose central panel depicts two naked men, is not an obscene picture. On the contrary, it’s a psychologically acute work depicting loneliness, and I insisted that it go in the show. Minutes before the private opening, I was told that the authorities had removed the central panel and put it in the back. As the visitors started touring the show, I rushed to the basement to fetch the missing panel, and had just put it up when the first visitors reached it. Unfortunately, I had to take it down by the time the exhibition opened to the public. Victories in this country are rarely unmitigated [smiles wryly].