It is a hot summer evening in 1923 on Emad el-Din Street, in the city’s storied El-Ezbikiya district — the cornerstone of a Cairo long extinct. Former French prime minister Georges Clemenceau, recently retired from political life in the aftermath of the Treaty of Versailles and the First World War, is escorted into the el-Hambra, an iconic music hall where the city’s well-heeled (and less so) regularly gather to indulge in music and a drink. Inside the smoky hall stands a busty, coquettish woman, gazing out before a spellbound audience. Her presence overwhelms. The assembled are mesmerized by her aloof, tragic sound — nothing short of seductive. The song ends, applause, and more applause. The apparently smitten Clemenceau turns to his Egyptian host and asks if he may buy the woman before him a bottle of the best champagne in the house.

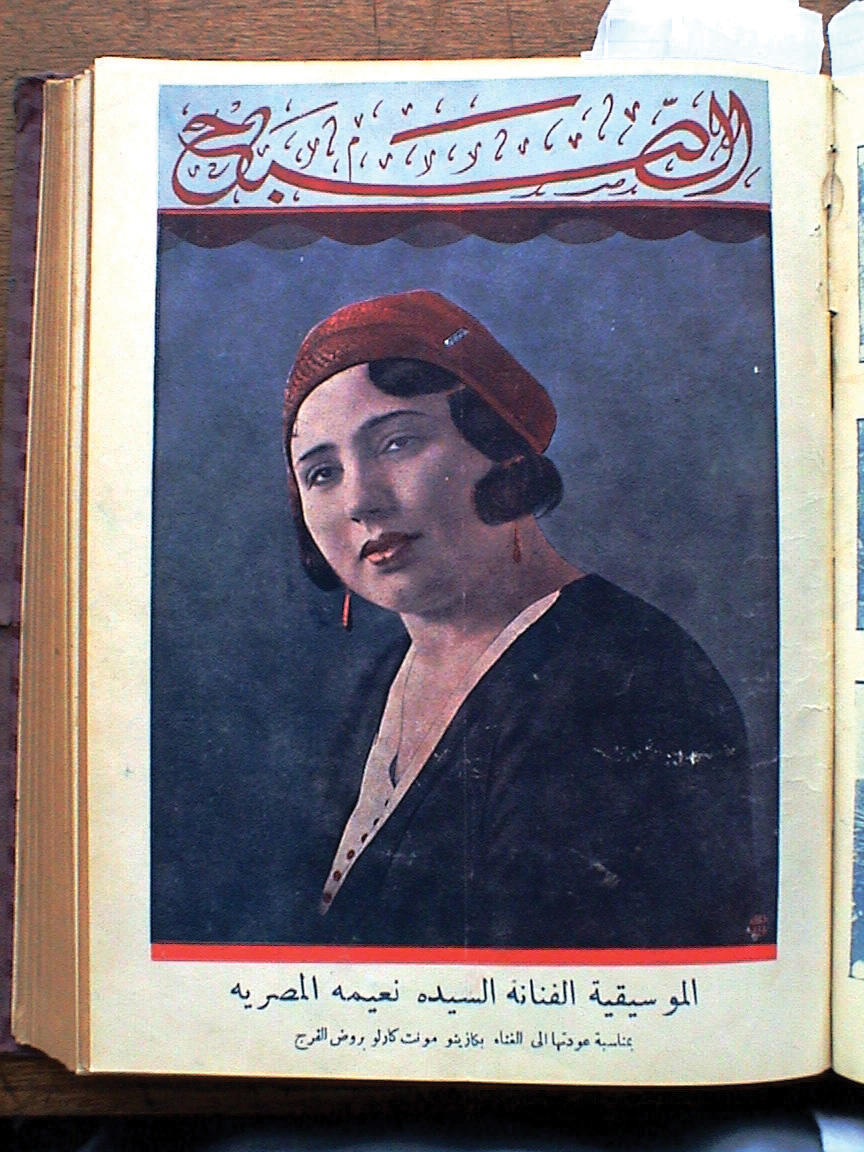

Though she may have been a head-turner in her time, few Cairenes today have heard of el-Hambra’s mystery woman — known then as Na’ima al-Misriyya. Generations later, her great-granddaughter, Egyptian-Canadian photographer Heba Farid, sits in a Cairo flat listening to one of the rare recordings left from that period, fiddling with a cigarette and discussing ambitious plans to create a platform to reintroduce the icon, who died in 1976. And it will begin here in Cairo, the city in which her great-grandmother built her reputation as one of the region’s most compelling, fiercely independent, and ultimately, unforgettable voices.

Na’ima al-Misriyya was born June 1, 1894 as Zeinab Mohammed Idris Sallam in el-Magharbillin, an area known today as Islamic Cairo. Her father was a wealthy, well-connected merchant of Moroccan origin, while her mother, the second of her father’s two wives, also hailed from a family of merchants in Upper Egypt’s Asiut. By the age of fifteen, Naima was married, and by sixteen had given birth to a daughter. Within a year, however, she had divorced her husband and left her child to move out on her own to the Cairo quarter known as Sayyida Zeinab. A family myth about that period tells of a Levantine neighbor known as el-Shamayyia overhearing the young mother crying and singing one day. So taken by her voice, the neighbor — herself a wedding performer (known then as an aalma) — encouraged and eventually trained her to sing. And so a career was launched. She would go to Aleppo for additional training in the period between 1911 and 1914.

Before long, al-Misriyya had made a name for herself with her singular voice, working alongside noted composers of her time, from Zakariya Ahmed and Mohammed el-Qasabgy to Sayyid Darwish. She performed in theaters and music halls from Beirut to Aleppo, Jaffa, and Baghdad. In addition to opening and single-handedly managing el-Hambra, she also performed in the Cairo district of Rod el-Farrag, at the music hall Alf Leyla wa Leyla (One Thousand and One Nights). A 1926 article in one of Egypt’s premier cultural and political magazines, Ruz el-Yusuf, proclaimed al-Misriyya one of the “most famous female singers” of her time. Listed along with Fatheyya Ahmad, Munira el-Mahdiyya, Tawhida, and the rising star named Umm Kulthumm, she was in good company. Her brand of music, referred to as taqtuqa, was not far removed from the pop of today — in effect a popular music that was accessible to all. By 1932, al-Misriyya’s voice was broadcast on the newly inaugurated Egyptian national radio. Some showered her with the title “queen of the phonograph” (maliket el-istiwanat).

As her career took shape, al-Misriyya married five times. By 1925, she had moved to the then-fashionable Cairo suburb of Chobra, where she lived with her daughter as well as her divorced sister and infant niece, Azziza, for many years. The Chobra home made for an epic setting, often serving as host to impromptu gatherings of musicians, composers, and friends.

In 1937, al-Misriyya’s life took a dramatic turn. The marriage of her daughter to a conservative, French-educated accountant proved fateful as he forbade her from singing, finding the life of an independent female performer immodest, even base. Most everything connected to her musical career was either given away or destroyed, from photographs to old recordings and performance bills. By the late 1930s, her name had ceased to appear in record company catalogues. And the rest, as it were, would become history as al-Misriyya spent the next four decades of her life largely in isolation, finally passing away in 1976 in her Heliopolis flat — never receiving the accolades that el-Mahdiya and, of course, Kulthumm, and other contemporaries were to receive.

Farid’s first memories of her great-grandmother are rooted in the image of a potent matriarchal figure. Her family’s emigration to Canada soon after her birth in Cairo meant that she would return to Egypt only periodically, every few years. Isolated pieces of her great-grandmother’s history accumulated in patchwork fashion — those, combined with regularly posted voice recordings from al-Misriyya recounting family events, musings, and sentimental nothings, created a complex picture. Her great-grandmother’s status as a performer, in the meantime, remained largely mysterious; bits and pieces would slip out in hushed fashion, particularly at times when Farid herself expressed a desire to pursue music as a hobby. The sole member of the family who could provide any substantive information about al-Misriyya’s life and career was her niece, Azziza. She, however, passed away two months ago. Thankfully Farid had recorded a number of conversations with her in the immediate months before her death.

Working full-time on the project since last year with backing from the European Union and Cairo’s Royal Netherlands Embassy, Farid’s efforts to reconstitute the lost story of her great-grandmother have exposed the tricky politics of archiving. In this field, entering the canon has never been easy. Needless to say, highlighting a popular musical style (taqtuqa) and, furthermore, the life and times of a stunningly contemporary, independent woman (al-Misriyya) was always likely to be a loaded proposition.

Indeed Farid’s initiative exposed a number of gaping holes in the state of conservation in the region at large. While there is a critical lack of resources devoted to music archiving, Farid and her team have encountered a number of difficulties in accessing existing archives, public and private alike. Everything from missing documentation to absence of organization has called attention to the need for investing in missing structures, from music archives to repositories for cultural magazines, newspapers, and photographs of the last century.

In the meantime, the scope of the project extends far beyond Egypt. At the moment, Farid has plans to send off researchers to Aleppo, Beirut, Jaffa, and Baghdad in hopes of collecting clues from former performance venues, as well as music lovers, both seasoned and amateur. In Baghdad, for example, a certain Hajj Abdelmuwain, who once ran the Umm Kulthumm Café (when central Rachid Street was a hopping cosmopolitan throughway), is known to be an aficionado of pre-Umm Kulthumm Egyptian music. People like Abdelmuwain may hold invaluable information, and seeking them out now is rendered all the more important because of their advanced age, as well as the current high level of instability in the region.

In addition to a book devoted to chronicling her great-grandmother’s life, Farid and her team are in the midst of producing a documentary film, as well as a music archive to be presented as a complete CD set. A limited number of fading 78 rpm recordings have been secured from music collectors, antiquarians, and the odd archive. Nevertheless, the most substantive collections remain locked away or inaccessible because of uncatalogued neglect, family squabbles, and impending court cases. This is Egypt, after all, where there is never a dearth of drama.

Out of the music archive initiative may come a musical resource center, which could ultimately safeguard the legacy of countless musical traditions for years to come. Renowned Sorbonne-based Arabist Frédéric La Grange has joined the project team and is providing invaluable help in this realm, while Grammy Award winner Harry Coster, who has recently restored rare Billie Holiday tracks, has also offered crucial advice in the realm of conservation.

And while today Emad el-Din Street may be far removed from the magic it was — lined with seedy beer bars, dilapidated cinemas, and over-mannequined clothing shops — crucial to Farid’s project is ensuring that we keep sight of what it once was. As an additional piece of the project, she and collaborators are constructing a map of the street, perhaps aptly referred to as Cairo’s version of Broadway, from the 1920s — a virtual exercise in urban archeology.

In the meantime, al-Misriyya’s musical legacy lives on, in veiled fashion. One day last week in an el-Ezbikiya café, her voice came cracking through the radio. Nobody in the café could identify the songstress, but near all within knew the words by heart. The song is Ta’ala ya shatter (Come on big boy) — recounting the tale of a young woman urging her lover to take her to the Barrages, a favorite hangout for lovers seeking discretion, asking him to bring “a bottle and have fun with her.” It seems that even today, al-Misriyya continues to defy popular notions of music history, the Arab world and, ultimately, women at large.

www.naima-project.org