Istanbul

11th Istanbul Biennial: What Keeps Mankind Alive?

September 12–November 8, 2009

This month, what, how, and for whom? The Zagreb-based curatorial collective behind the 11th Istanbul Biennial, conducted a sort of séance, summoning up a historical ghost with whom, it turns out, an exhibition of this size could only vaguely engage. The Biennial took its name from a line in Bertolt Brecht’s 1928 musical The Threepenny Opera (“What Keeps Mankind Alive?”). But Brecht’s specific inquiry was less important to the exhibition than the broader principle evoked by the famous Marxist figure. As the curators put it, “Is it not possible to think of art the way Brecht understood theater — a mode of ‘collective historical elucidation,’ an apparatus for constructing truth rather than what amounts to a viewing feast for the bourgeoisie?”

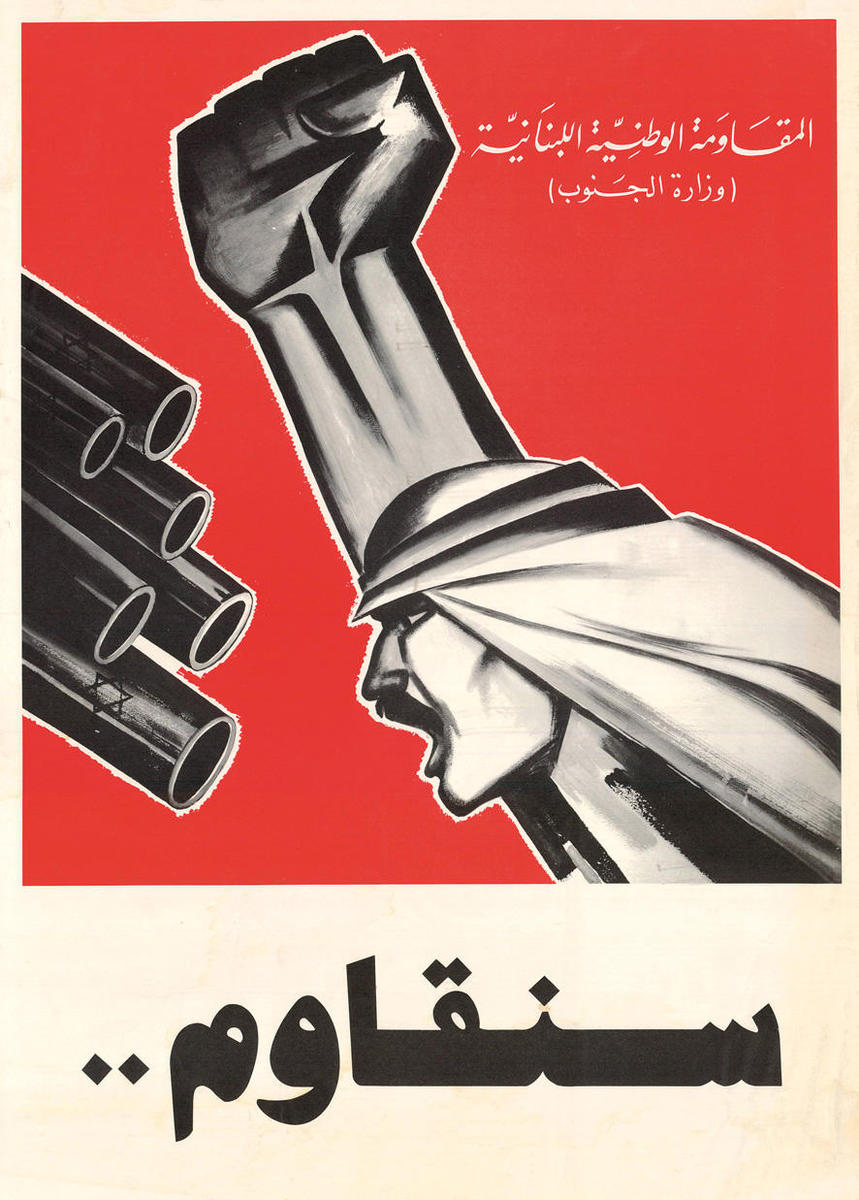

Luckily, WHW rooted that abstract inquiry in some solid typography and an unambiguous stance on the role of identity politics in international biennials. This year the Istanbul Biennial brand was all (Communist) red and (anarchic) black, blocky lettering with Cyrillic leanings, and the occasional star. The schema played on the curators’ own regional affiliation (“just East of the West”) to emphasize the seemliness of their involvement in this equally “peripheral” endeavor. It’s easy to knock the marketing device, but the simple question of regional affiliation was actually one of the primary ways WHW made good on their promise to “construct new truths.”

Even today, after the hybridity fest of the 1990s and more recent bombast about “globalization” (see Hou Hanru’s 2007 Istanbul Biennial), non-Western artists who trained outside the West, or who continue to live elsewhere, are rarely afforded the same status as EuroAmericans at international biennials. According to Chin-Tao Wu, in an article called “Biennials Without Borders” in the New Left Review, well over 90 percent of artists exhibited at Documenta before Okwui Enwezor’s 2002 edition were born in North America and Europe, reaching a record 96 percent in 1972. Even Enwezor’s exhibition, which featured forty percent non-Western artists, included a total of 76 percent living in Europe or North America.

What Keeps Mankind Alive? offered a compact statistical retort to these circumstances, presented in the exhibition guide, catalog, and a set of display panels: artists by country of origin: From the West: 28%. From the “Rest”: 72%. artists live and work: In the West: 45%. Elsewhere: 55%. These statistics were accompanied by an “upside-down” map where the former East became the West, reversing the starting point in a left-to-right reading of the world. (The map was colored red to indicate the artists’ origins.) WHW was hardly suggesting that we hunt down a trove of undiscovered, non-Western artists as new fuel for the grandes expositions of the twenty-first century. The four-member, all-female collective — themselves a bit of a statistical anomaly — simply asked: What if someone actually did it, for once?

Hou Hanru’s 2007 Istanbul Biennial, ‘Not Only Possible But Also Necessary: Optimism in the Time of Global War,’ was both notoriously overblown and underwhelming. WHW’s biennial was diametrically opposed: evidence that simple premises, realized well, can be revelatory. Artworks were shown in the massive waterfront customs depot Antrepo no. 3, a former tobacco warehouse in the historically European quarter of Galata, and an old Greek school that shut down in the 1980s for lack of students. A series of superlative “historical” works — spanning the late Sixties through the early Eighties — risked stealing the show. Made by artists like K. P. Brehmer, Cengiz Çekil, Nam June Paik, Michel Journiac, and Hans-Peter Feldmann, the older artworks, many on paper, were as concise, clear-eyed, and open to humor as the biennial’s proliferation of recent videos were lengthy and prone to taking themselves too seriously. But by distributing multiple artworks by single artists across the exhibition sites, WHW avoided locking individual works into strict relational categories — “historical,” “contemporary,” or otherwise.

Five very short black and white films made by the Armenian artist Hamlet Hovsepian in the 1970s were spare, unexpectedly affective studies of quotidian gestures — yawning, scratching one’s back, washing one’s hair. Head (1975) framed the top of Hovsepian’s head closely, anonymizing him as his hands worked the lather around and around in a dark, viscerally evocative mass of hair. In its unceasing repetition, body and action near abstraction, this quotidian act began to feel decidedly bleak. Yawning (1975) was more lighthearted. Hovsepian — long-haired, in a suit cut for that era alone — sat in a chair facing the camera, docilely waiting for a yawn to come on. It did: contagion involved the viewer in the loop.

The contemporary works coalesced — or, equally tellingly, dissolved — around recurring figures like German artist K. P. Brehmer (1938–1997), who appeared in all three venues. You’d assume Brehmer’s graph-and map-based illustrations on the movement of armed forces in the Vietnam War, the price of zinc and potatoes in Germany, or the year-long changes in the “soul and feelings of the worker,” would be flatly boring in the face of flashier contemporary offerings. But Brehmer’s hand-drawn works, made between 1968 and 1980, acted as a critical yardstick for later ones of a similar conceptual persuasion but more contemporary style of execution. In three pieces from 2009, Marko Peljhan reconstructed armed forces movements on the day of a Bosnian massacre (Territory 1995); the artist pair Bureau d’Études provided a global overview of the Administration of Terror, wherein a web of arrows tracked international intelligence operations from the 1950s onwards; and the duo Société Réaliste created an impenetrable alphabet of international borders turned into ideograms (Ministry of Architecture: Culture States). Like Brehmer, these contemporary artists aimed to convey visually the trajectory of vast amounts of goods, money, people, and power. Yet this contemporary, computer-generated “mappings” lacked the simple legibility of Brehmer’s hand-drawn work. The Internet era has provided us so many ways to “plug” concepts in to imagemakers and datacrunchers; one can’t help but mourn the thinking and design-time abandoned in the process.

Standout works were often video, in a program heavy on video overall. At Antrepo, Rabih Mroué’s I, the Undersigned took on the genre of the public apology. On one screen, Mroué, stoically facing the camera, enumerated a long list of things for which he was sorry, while a second screen featured his statements in scrolling text. Mroué’s apologies were couched in a sort of legalese and addressed to those whom he may have harmed (knowingly or unknowingly, in circumstances of any sort). Beneath his remorse lay the implied confessions to deeds whose dimensions we could only imagine. The precision of Mroué’s statements slowly dissolved, eventually collapsing into one ongoing sentence that rang with futility: “words, words, words, words, words… ” At the tobacco warehouse site, the Russian collective Chto Delat? also looked askance on the empty symbolism of political rhetoric, in a short, satirical operetta titled Perestroika Songspiel — The Victory Over the Coup (2008). Scenes of typical citizens gearing up to change the world by protesting in the local square alternated with musical interludes featuring a six-person choir. The choir’s ironic lyrics were at odds with the music to which they were set: “Pinochet! Pinochet!” was sung as a blissful soprano; “Chechnya! Chechnya! Chechnya!” appeared as a resounding finale; and “Hatred for authority, that’s the ticket!” set the driving rhythm of a militaristic tune. At the Greek school venue, Ruti Sela and Maayan Amir’s Beyond Guilt #2 (2004) encapsulated a disturbing conflation of masculinity and militarism in a documentary filmed in a Tel Aviv hotel room. Having invited a series of young Israelis to the hotel through an online sex chatroom, the two women proceeded to interview them about their obligatory military service. The male posturing, displays of “weaponry,” and tangled attitudes towards sex and violence that emerged made for riveting, uneasy viewing.

As historian Omnia El Shakry pointed out in her catalog essay, contemporary non-Western artists are almost always presented as “localized,” “particular,” or driven by region-based problems that are specifically “Uzbek,” “Lebanese,” “Russian,” or “Turkish.” By integrating a significant body of artists from, say, Armenia, Egypt, Uzbekistan, or Croatia, into the 11th Istanbul Biennial, WHW shook this standard. So, to answer the question WHW asked, “What would happen if one were to draw upon an unprecedentedly non-Western demographic to produce one of today’s major international biennials?” Actually, nothing wildly different. Nothing happened that wouldn’t also have happened at any well-installed, discerningly selected, and historically grounded exhibition of contemporary artists from anywhere else in the world. Yet WHW’s gesture nonetheless carried significance for biennial practice in general.