Istanbul

10th Istanbul Biennial

Various venues

September 8–November 4, 2007

Visitors to the tenth edition of the Istanbul Biennial this year could easily have been overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of artwork on display. Parallel events throughout the city, along with a hefty biennial program featuring over one hundred artists, made for an art-going experience that was more daunting than inspirational. Curator Hou Hanru’s ambitious title set the tone: ‘Not Only Possible, But Also Necessary — Optimism in the Age of Global War.’

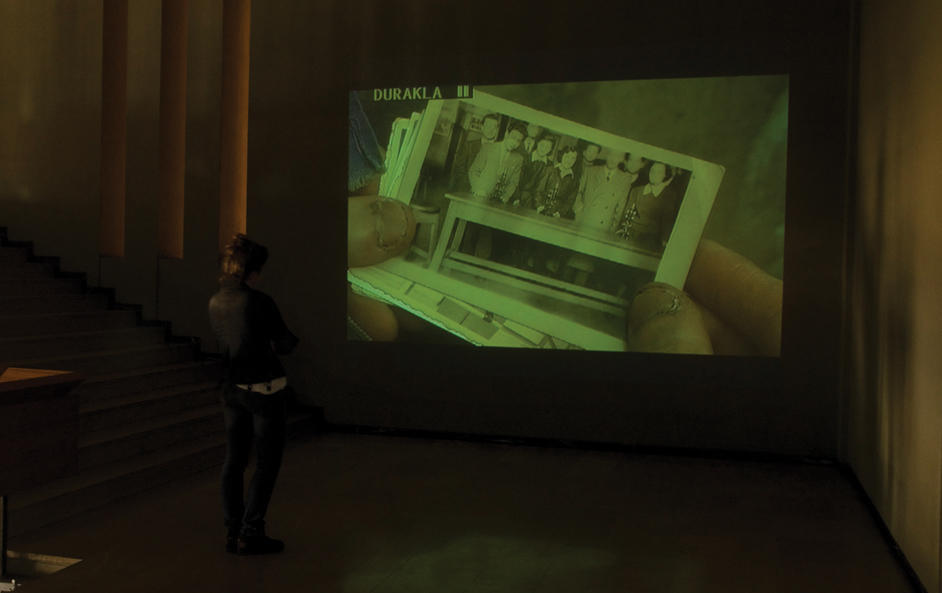

The biennial’s official exhibition was divided among three venues, two near the main contemporary cultural center of the city and one in an underused market area close to historical sites and next to the city’s ancient aqueduct. Antrepo No 3, a cavernous customs warehouse no longer in use, hosted works exploring “global trading, migration, and border crossing.” The Ataturk Cultural Center (AKM) hosted ‘Burn It or Not?,’ an exhibition focusing on “questions of social progress of modernity,” referring to a current controversy about the building’s own fate. Meanwhile, the Istanbul Textile Traders’ Market (IMC) opted to study “models of production, consumption, and economic development.”

At times the heavy-handedness of thematic headings for each venue bore down on the selection of works. Of the three venues, Antrepo No 3 provided the most cohesive offering and also functioned as a hub of the biennial. Unfortunately, while the overall installation of the building was entertainingly maze-like, competing audio works and a series of cumbersome, large-scale presentations created a bombardment of visual texture and sound. The audio component of works such as those by Gimhongsok and Ramon Mateos, similar in aesthetic and concept, were at times impossible to distinguish. Cao Fei’s RMB City, a proposal for a virtual zone in the style of Second Life, took up valuable exhibition space with brash computer-generated imagery on ad-style banners. Similarly, Alexandre Périgot’s Soundborders, an interesting collection of musical compositions, was hamstrung by the series of rotating floor discs that one had to negotiate in order to hear them. These more dominant, bulky installations overshadowed subtler works that, when given space, surfaced as the sought-after moments of optimism.

Justin Bennett’s noise mappings, a series of precise cacophonies of collected sounds from his time spent as an artist-in-residence in Istanbul, conveyed the shifting history of a city in flux. One of his pieces left the entrance stairwell vibrating with the sum of Istanbul’s urban pulse, conveying a sense of occasion and anticipation for ascending visitors. His other sound installations were more modestly presented on headphones in locations that allowed expansive views of the Bosporus, transporting audiences beyond the city’s physical grasp. Jennifer Allora and Guillerma Calzadilla’s There Is More Than One Way to Skin a Sheep (2007) featured the tulum, a folk wind instrument from the mountainous Kaçkar region of Turkey, evoking the increasing numbers leaving the eastern part of the country and moving to its main cities. In the video, the tulum’s notes were played through a bicycle wheel to add air to its flat tire. It is a melancholic, if not poetic, tale of migration.

A work that was almost lost in the shadow of larger installations was Emre Hüner’s Panoptikon (2005). Composed of a selection of drawn objects united in a video of imaginary animated worlds, his colorful sets hearkened back to Ottoman-era miniatures as well as to scientific invention and war. In the Ataturk Cultural Center another of Hüner’s video works, Boumont (2006), was more constructively installed. The video anticipated a pessimistic future; a dark trawl through the city’s many deserted industrial areas served as a powerful antithesis to the building’s (now dated) modernist hopes and principles. Incidentally, AKM is one of the most impressive works of modern architecture in the city, and while the biennial offered an opportunity to bring its impressive interior to life, the didactic and visually repetitive nature of some works there proved draining.

The exhibition at IMC presented a similar problem of overcrowding in a complicated context. Artist Chen Chieh-jen was one of few who managed to overcome these constraints of space, positioning himself in one of the market’s main thoroughfares and selling pirated versions of his own videos.

And that was only a taste of the biennial proper. Although the live arts potential of AKM was overlooked, there were several performance events during the opening days that were not to be missed. At Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center, an event initiated by artist Cevdet Erek saw his band Nekropsi playing on different levels of the building. In those spaces, wired so that each artist could play his instrument individually, audiences could experience the band as a series of intimate and very personal interventions. Meanwhile, all four parts came together in unison via speakers installed in the courtyard.

Platform provided a good portion of the other highlights, including an open studio day for artists-in-residence, along with Mladen Stilinovic’s gallery show ‘Subtracting of Zeroes,’ which managed to represent with humor political trauma and upheaval in works composed of an array of bank notes, found objects, photographs, statements, and sums all adding up to zero.

Istanbul’s newest commercial gallery, Rodeo, is located in an old tobacco warehouse that was one of the venues of the 9th Istanbul Biennial. The revamped space presented its first exhibition with exquisite new commissions by Hüseyin Alptekin and Christodoulos Panayiotou, as well as a permanent installation by Ahmet Ögüt of poured asphalt that turned the ground floor into a generous play area for local children. The city’s sprawling Istanbul Modern Museum featured the last twenty years of the biennial’s history with a chronological, best-of-the-best approach, while ‘Modern and Beyond,’ the inaugural exhibition at santralistanbul, surveyed the last fifty years of art in Turkey. More straightforward in scope, these exhibitions helped to contextualize the various art scenes of Istanbul — a critical engagement with the local element so often missing from biennials worldwide. Finally, the more personal and very local art initiative PiST strove to bring everything together by providing information on artists as well as producing LiST; their map and listings brochure were coveted like gold by those trying to navigate the dizzying maze of art strewn across the city.

www.iksv.org/bienal10